By Kevin Gorman

By Kevin Gorman

Executive Director

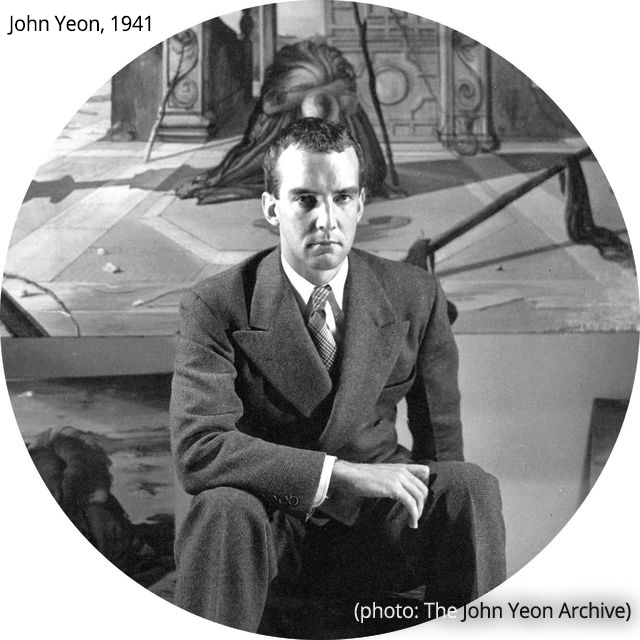

Leaders in our modern culture are often those people most comfortable in the spotlight and eager to build their personal brand. But if you are interested in learning more about one of Oregon's most effective, under-the-radar conservation leaders, you have a little over a week to make your way to the Portland Art Museum for Quest for Beauty: The Architecture, Landscapes, and Collections of John Yeon. The exhibit and accompanying book, John Yeon Landscape (available for purchase on our website), were created by Randy Gragg, former director of the John Yeon Center. Randy is masterful in peeling back the layers of this deeply private man and I encourage you to dig deep into both the exhibit and the book —as my words just scratch the surface of the work of John Yeon.

John Yeon (Yeon rhymes with John) was an anomaly in the Oregon conservation movement. First, he was ahead of his time. Born in 1910, he was the son of John Baptiste Yeon, a Canadian logger turned real estate magnate who served as roadmaster of the Columbia River Highway for a salary of $1 a year. The younger John grew up watching his father, along with Sam Hill and Sam Lancaster, painstakingly build a road through the wild Columbia Gorge. The elder Yeon built the road to standards unheard of at the time: it was the first paved road in the Pacific Northwest and followed a route to highlight waterfalls and scenic vistas while limiting the number of trees cut to complete the task. Natural beauty superseded commerce, a theme that would continue through young John’s life.

Conservation activism started early for John. Barely into adulthood, he learned of a plan to build a dance hall on Chapman Point, a promontory on Cannon Beach that juts out into the Pacific Ocean. Today, Chapman Point is front and center in one of the most photographed vistas in Oregon, the Pacific coast as seen from Ecola Beach State Park. John stopped the dance hall and for the remaining sixty years of his life nurtured the property. Today, it is owned by Oregon State Parks and named the John Yeon Natural Area.

John’s conservation ethic caught the attention of Oregon Governor Julius Meier, whose summer home Menucha near the Vista House is now a conference retreat center. Meier was a family friend and named John to the Oregon State Parks Commission at the tender age of 22. A few years later, as Franklin Roosevelt sought to electrify the West with the building of the Bonneville Dam, Portland utilities sought to gain an edge over their Puget Sound rivals and worked to ensure that power from the dam would be priced concentrically, meaning the closer you were to the dam, the cheaper the power would be. Local businesses touted that the Gorge could become the “Pittsburgh of the West,” with steel mills lining the Columbia. John advocated strongly for uniform pricing and used every connection he had to make his case. He eventually won and the threat of industrial development in the Columbia Gorge subsided.

John’s conservation ethic caught the attention of Oregon Governor Julius Meier, whose summer home Menucha near the Vista House is now a conference retreat center. Meier was a family friend and named John to the Oregon State Parks Commission at the tender age of 22. A few years later, as Franklin Roosevelt sought to electrify the West with the building of the Bonneville Dam, Portland utilities sought to gain an edge over their Puget Sound rivals and worked to ensure that power from the dam would be priced concentrically, meaning the closer you were to the dam, the cheaper the power would be. Local businesses touted that the Gorge could become the “Pittsburgh of the West,” with steel mills lining the Columbia. John advocated strongly for uniform pricing and used every connection he had to make his case. He eventually won and the threat of industrial development in the Columbia Gorge subsided.

In the 1960s, his love of landscape architecture and the Columbia Gorge merged. A property he had eyed in 1950 came on the market in 1965 and he purchased the 75-acre former farmstead he came to call the Shire. A one-mile long Columbia riverfront property, the Shire sits directly across from Multnomah Falls. The property John purchased was part swamp, part blackberries and lots of scrubby trees, but it was the surrounding landscape that sold him. As he wrote a friend, “If you can’t own the floor of the Yosemite Valley, this may be the next best thing of the sort.”

John spent more than a decade bulldozing, grading and sculpting the Shire to create a fairy-land escape. Part cultured English garden, part wild shoreline, the Shire became a shrine to natural beauty, both wild and manmade. As he worked to preserve his slice of the Gorge, he saw a rise in subdivision development occurring, particularly on the Washington side of the Gorge where there were no land-use rules. He knew the Gorge was equal in beauty to many of our country’s national parks and began advocating for national park status. But he understood that such an endeavor would require a non-profit organization to build a base of supporters and lead the charge to call for a national park in the Columbia Gorge. John also understood he was not the person to lead that organization. As an advocate, John’s volatile impatience was well known. He infamously chastised Oregon Governor Atyieh in a private meeting over Gorge protection and then felt obligated to follow up with a long, apologetic letter. John knew he needed to find a leader with his passion but not his temperament.

John spent more than a decade bulldozing, grading and sculpting the Shire to create a fairy-land escape. Part cultured English garden, part wild shoreline, the Shire became a shrine to natural beauty, both wild and manmade. As he worked to preserve his slice of the Gorge, he saw a rise in subdivision development occurring, particularly on the Washington side of the Gorge where there were no land-use rules. He knew the Gorge was equal in beauty to many of our country’s national parks and began advocating for national park status. But he understood that such an endeavor would require a non-profit organization to build a base of supporters and lead the charge to call for a national park in the Columbia Gorge. John also understood he was not the person to lead that organization. As an advocate, John’s volatile impatience was well known. He infamously chastised Oregon Governor Atyieh in a private meeting over Gorge protection and then felt obligated to follow up with a long, apologetic letter. John knew he needed to find a leader with his passion but not his temperament.

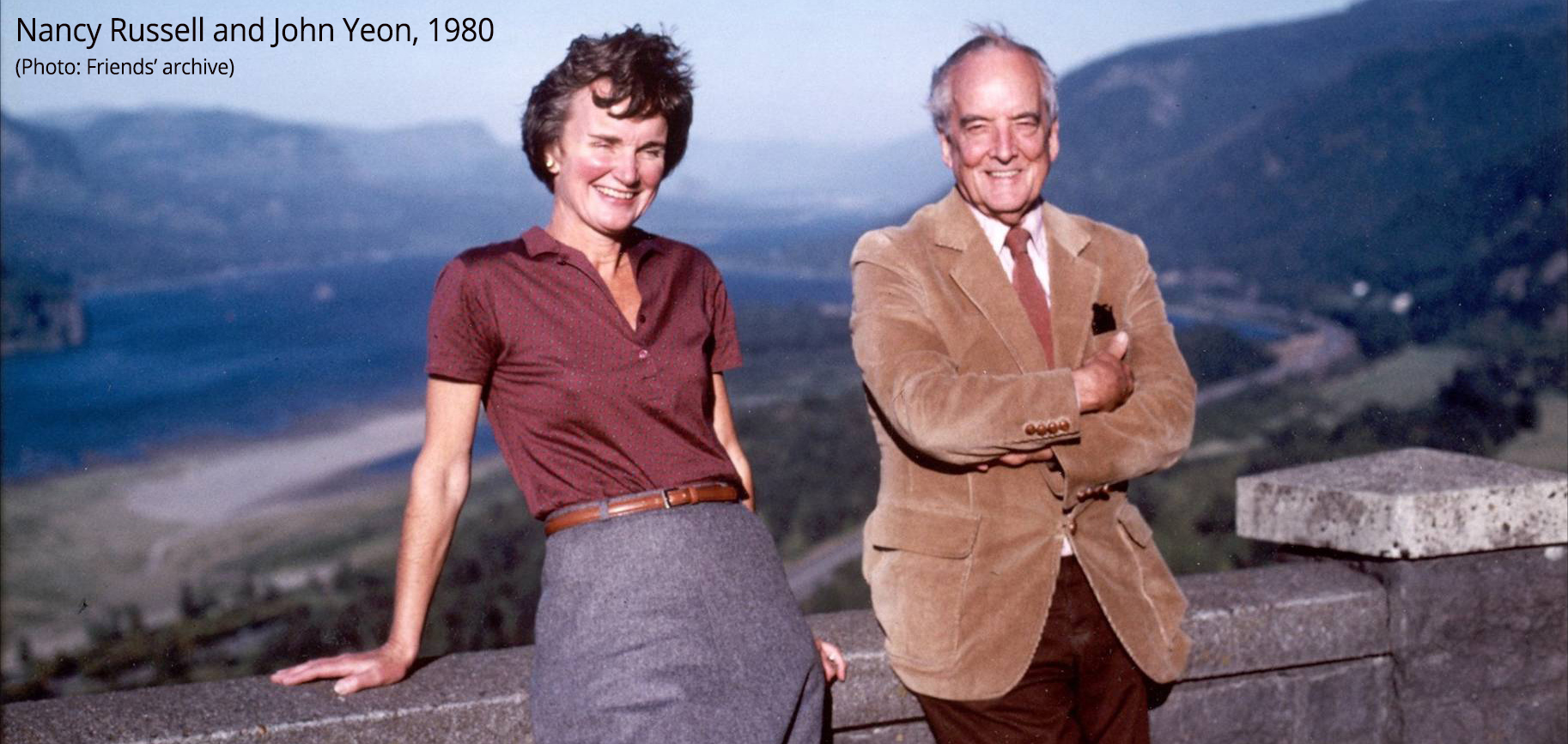

John found that leader in a Portland homemaker with a deep knowledge for Gorge wildflowers. Nancy Russell didn’t have a resume to take up such an enormous challenge as she had no fundraising or political experience and had never served on a non-profit board. John, however, was drawn to Nancy by her passion for the Gorge and her willingness to not only stand in the spotlight but spar with adversaries. Nancy also had a deep competitive spirit honed from years on the tennis courts. She simply hated to lose. It was icing on the cake that Nancy was a republican as was the majority of Oregon and Washington’s congressional delegations.

John used every tool he had available to “woo” Nancy to accept this challenge. He invited Nancy and her husband Bruce to the Shire for an elegant meal on the Columbia across from Multnomah Falls. True to John’s perfectionist streak, he cancelled their first dinner and then a second as he feared the light and evening would not be as spectacular as hoped. The third time was a charm and as John served a picnic dinner on fine china and Asian rugs, he told Nancy of the opportunity they had to protect the Gorge for generations to come. As he spoke, the sun set and turned the Gorge walls pink. The moon rose above Multnomah Falls. Nancy Russell was entranced and that dinner set in motion the creation of Friends of the Columbia Gorge and eventually the creation of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

In the early years, John mentored Nancy and she quickly picked up his sense of natural ascetics and a “parks” perspective of conservation. His vision guided her and shaped her thinking through her final days. While the story of John Yeon and Nancy Russell is one of the great conservation stories of our lifetimes, it is also bittersweet. As Nancy and her fledging organization pushed for Gorge legislation, the political realities set in. While President Carter’s staff expressed interest in 1980 in a Gorge national park, President Reagan came in 1981 and had no interest in creating new national parks. Oregon’s Senator Mark Hatfield became the most powerful Senator in Washington DC and his allegiance was firmly with U.S.

Forest Service management of the Gorge versus National Park Service management. Friends of the Columbia Gorge, faced with prospect of no legislation or a National Scenic Area designation with the U.S. Forest Service managing the lands, opted for the latter. John Yeon, ever a perfectionist and National Parks advocate, was deeply discouraged. While he did not oppose the legislation, he could never bring himself to provide full-throated support. He died in 1996, well before many of the impressive accomplishments the National Scenic Area made possible.

Forest Service management of the Gorge versus National Park Service management. Friends of the Columbia Gorge, faced with prospect of no legislation or a National Scenic Area designation with the U.S. Forest Service managing the lands, opted for the latter. John Yeon, ever a perfectionist and National Parks advocate, was deeply discouraged. While he did not oppose the legislation, he could never bring himself to provide full-throated support. He died in 1996, well before many of the impressive accomplishments the National Scenic Area made possible.

The Shire is now in the hands of the University of Oregon School of Architecture. It is, for the most part, maintained as John desired and occasionally is opened to the public.

The Portland Art Museum exhibit on John Yeon closes Sept. 3. Randy Gragg’s book of John’s conservation work at the Oregon coast, in the Olympics and of course, in the Columbia Gorge, is available for purchase at our website.