Forest fires around the region blanketed us in a smoky haze this summer. The burnt tinge in the August air evoked the 2017 fires in the Columbia River Gorge that ravaged the forest sheltering Eagle Creek, threatened Multnomah Falls Lodge and forced evacuation of Cascade Locks.

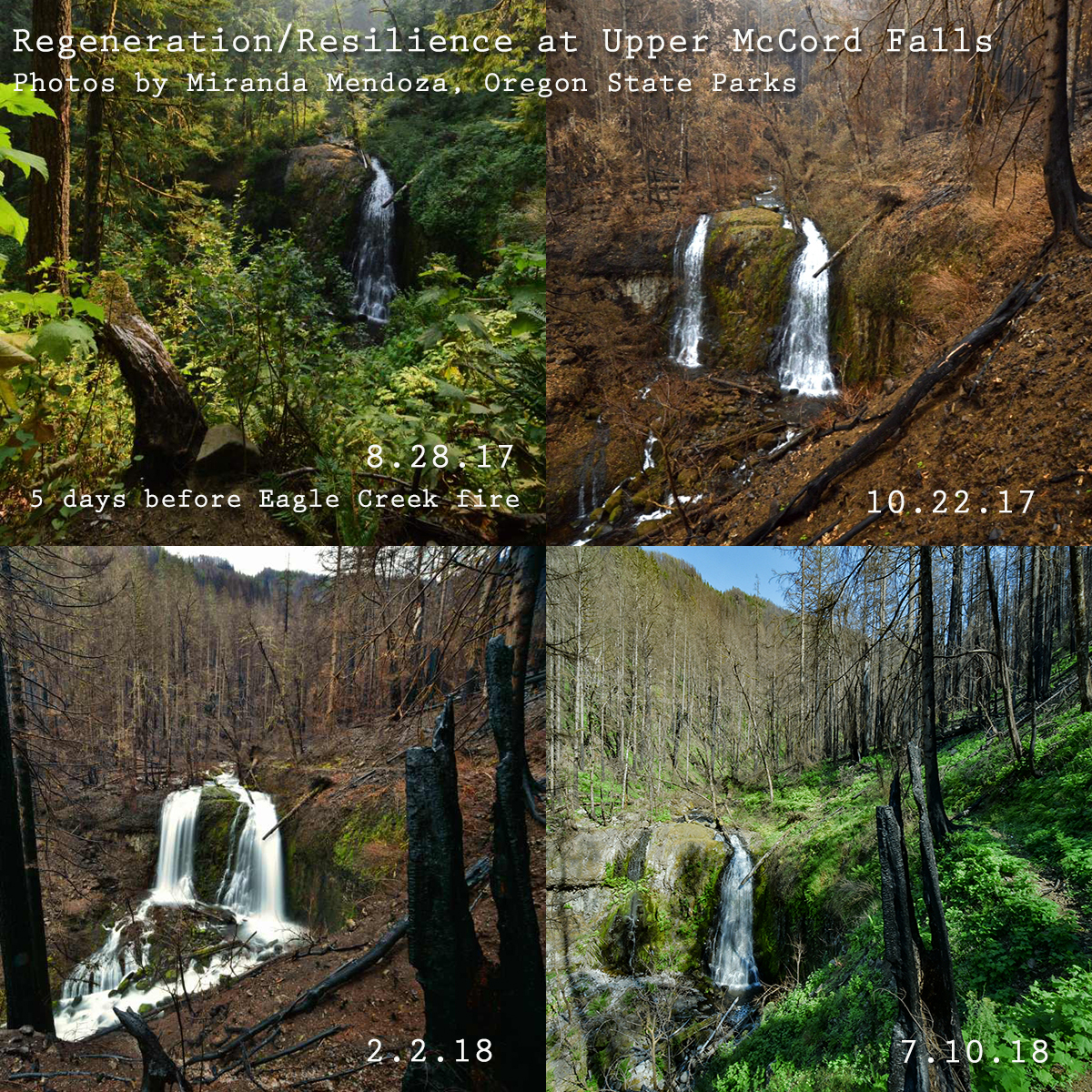

Before the Eagle Creek fire, residents along the western end of the Columbia Gorge hadn't experienced a major fire in their lifetimes. They mourned the scarred landscape. Yet historical perspective offers solace: The forest will, in time, recover in a burst of even greater biological diversity.

"Anywhere you go in the Gorge area, if you step off the trail, you're going to get down to a layer of charcoal. The bigger, older trees have burn scars from 100 years ago. The Eagle Creek fire was not unique. It's yet another fire in a historical pattern of fires in this area," said Michael Lang, conservation director for Friends of the Columbia Gorge.

Infrequent but ferocious

Fire is a part of a natural cycle, something that's easy for those of us west of the Cascades to forget. That's because these forests rarely burn, earning them the nickname "asbestos forests," said University of Washington professor Jerry Franklin. He's a world-renowned forest ecologist who has extensively studied the landscape ravaged by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

In these damp forests, thick with towering firs and undergrowth, fires are few and far between.

"People seem to think that forests everywhere have one kind of relationship to fire. Our Douglas fir-western hemlock forest in western Oregon and Washington—it's quite a unique system," Franklin said.

"It is their nature to burn very infrequently, but when they do, it's going to be an intense fire that's almost impossible to control. These forests are adapted to this. They have a capacity to restore themselves, but it takes a very long time to do it." Franklin and others believe that climate change will increase the frequency in Douglas fir and hemlock forests.

The largest recorded fire in the western Gorge struck in 1902. The Yacolt Burn may have been named for a Washington town, but it actually began on the Oregon side of the Columbia River in Bridal Veil before it spread to Cascade Locks and then jumped across the river. It burned 238,920 acres in Clark, Cowlitz and Skamania counties. It wasn't the only fire raging at the same time. About a million acres burned around the region that year, Franklin said.

The Yacolt Burn, like the Eagle Creek fire, was human caused: It's believed to have been caused by loggers burning slash. And as in the 2017 Gorge fires, hot September east winds stoked the flames.

The Yacolt Burn, like the Eagle Creek fire, was human caused: It's believed to have been caused by loggers burning slash. And as in the 2017 Gorge fires, hot September east winds stoked the flames.

"We are going to have to recognize the fact that because we have these productive forests, we are going to have very ferocious fires," Franklin said.

Appropriate action

As the climate changes, we can expect more rainfall and longer, hotter, drier summers, Franklin said. So fires in western Oregon and Washington forests that had occurred every 200 to 400 years will become more frequent, he said. We just don't know how frequent.

"There isn't a darn thing you can do to fundamentally alter the nature of those forests. It's something we're going to have to learn to adapt to," Franklin said. "We can't change it."

When people see a beloved area damaged by fire, there's an urge to take action, to try to fix it by cutting trees and replanting, and to grab up the economic value of the wood. Franklin rejects this notion.

"It's almost criminal to think in those terms. The damage you would do in a logging operation to would be unbelievable," Franklin said. It would cause short-term damage from operating trucks and heavy equipment in the burned area, but also long-term damage by depriving the forest of the nourishment it needs to regenerate.

"Going in to do post-fire clear-cut logging and planting is the most destructive thing you can do," Lang concurred.

While these experts argue against interfering with natural recovery after a fire, they do see an appropriate course of action beforehand.

"We need to be aware these fires can happen. People who live out in the forest need to understand the risk and tests steps to reduce those risks," Franklin said. "Aggressive detection and suppression of fire is an absolutely appropriate thing to do."

"We need to be aware these fires can happen. People who live out in the forest need to understand the risk and tests steps to reduce those risks," Franklin said. "Aggressive detection and suppression of fire is an absolutely appropriate thing to do."

Fire mosaic

The Eagle Creek fire, at nearly 49,000 acres, was a fifth the size of the historic Yacolt burn, and only 15 percent of that area suffered severe damage. In some areas, fire smoldered along the forest floor, damaging tree roots, and in other areas, it moved along the crowns of trees, completely torching them. Hardwoods resist fires, while the resins in firs are more flammable. The varying levels of damage form a mosaic.

"There's a whole spectrum of effects in a fire. It's not uniform," said John Cowan, an Oregon State Parks ranger in the Columbia Gorge. "The notion that all fire is bad is not true, but fires still have consequences."

The Eagle Creek fire burned off moss and shrubs that stabilized rocky slopes, including the one above Multnomah Falls Lodge, so the U.S. Forest Service's Burned Area Emergency Response team installed a fence to catch boulders that threatened the historic building. After the fire, Cowan, an arborist, tagged 500 trees from Crown Point to Angels Rest as public-safety hazards that needed to be removed in order for roads and trails to reopen.

But absent a hazard, forest ecologists prefer to let the forest heal itself. Even a burned tree has a role to play in the ecosystem. If damaged but not immediately killed, the tree will likely die within two years, according to the Forest Service's Pacific Northwest Research Station. The snags provide habitat for wildlife. When they ultimately fall, they decompose and nourish the soil.

"As a policy, we want to leave the wood," Cowan said. "Over the lifetime of a tree, it secures a great deal of carbon. Microfauna, mushrooms and certain micro-organisms make use of that wood. Nurse logs support a community, stabilize the environment and create soil. That's the purpose of decay. It's a biological process. The circle of life — that's what we're seeing here."

'An explosion of biota'

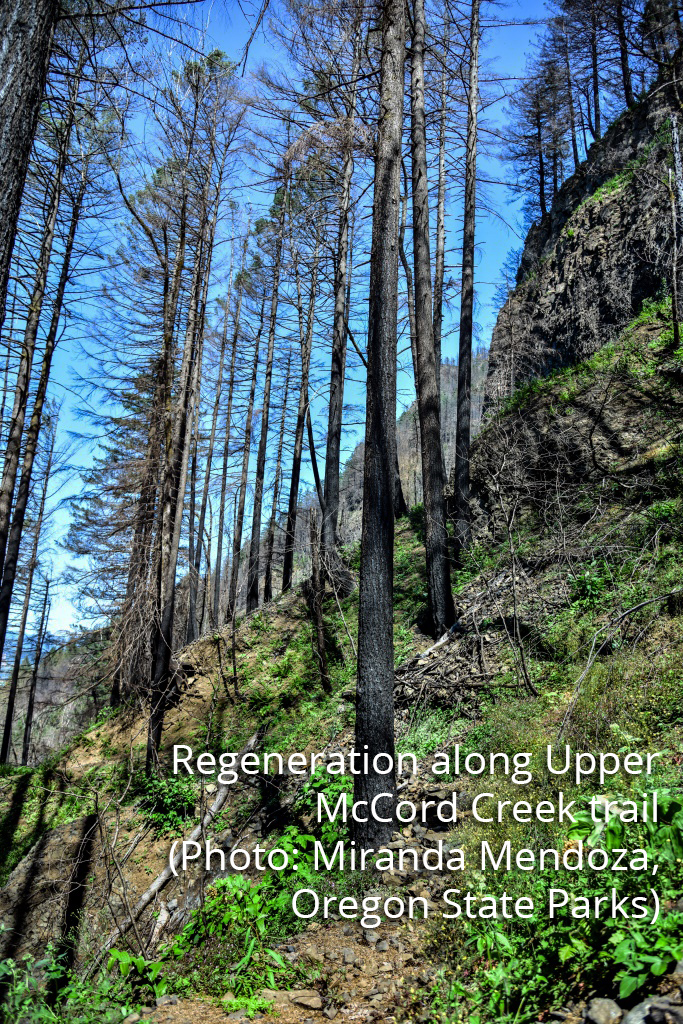

Ferns and mosses are the first to paint green on the blackened landscape. Mushrooms, wildflowers and berry-laden shrubs sprout. Maples, oaks and fir seedlings peek out of the ground. Insects feast and thrive. All this provides a banquet for birds.

The U.S. Forest Service has been sharing evidence of rebirth in the Eagle Creek burn on its Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Twitter feed. Bright yellow monkey flower bloomed this spring and summer. Green ferns are popping out of charred tree trunks. Black-beaked woodpeckers are feasting on wood-boring insects eating burned trees. Robins are building nests.

The U.S. Forest Service has been sharing evidence of rebirth in the Eagle Creek burn on its Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Twitter feed. Bright yellow monkey flower bloomed this spring and summer. Green ferns are popping out of charred tree trunks. Black-beaked woodpeckers are feasting on wood-boring insects eating burned trees. Robins are building nests.

Fire clears a path for greater ecological diversity, experts said. Douglas firs tend to dominate forests west of the Cascades because they form a closed canopy, shading out everything below.

"I've been in love with old-growth forests my entire life. But when it comes to biological diversity and richness of life, the highly disturbed fire landscape puts old growth to shame," Franklin said. "There's a whole lot of species that need that open condition that is represented in these big burns."

The best course of action after a fire, Franklin said, is to "get out your binoculars and your guide to animal tracks and enjoy the explosion of biota that's going to happen there."

Erin Middlewood is a writer from Vancouver, WA. She enjoys exploring the Columbia Gorge with her husband and two sons. She's especially fond of the Nancy Russell Overlook at Cape Horn. Follow her at erinmiddlewood.com or @emiddlewood on Twitter.