By Nathan Baker

Senior Staff Attorney

September 9, 2024

After more than two decades, the plans to build the Whistling Ridge Energy Project, an industrial-scale wind energy project once proposed in the central Columbia River Gorge, have finally been ended. The state-issued permit for the controversial project was deemed “expired” in a written order issued on July 17 by the Washington Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council (EFSEC) after the agency heard from various parties including Friends of the Columbia Gorge.

As far back as 2002, the Whistling Ridge project posed serious threats to scenic, natural, cultural, and recreational resources as well as local communities in the special and unique place where the Cascade Range intersects with the Columbia River Gorge. Proposed along the boundary of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area and within an area designated for the protection of the imperiled northern spotted owl, the Whistling Ridge project would have (among other problems) marred world-class scenery and harmed endangered species habitat, with little to no benefit to the people of the Pacific Northwest.

From the moment the project was first unveiled, Friends and allies stayed involved and opposed the poorly designed project at every step of the process, including litigation before the Washington Supreme Court and federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Through our tireless advocacy and litigation, Friends ensured that the project, once proposed to include up to 85 wind turbines, met its demise in three phases over the course of 15 years: 35 proposed turbines were rejected in 2009, 15 additional turbines were denied in 2012, and permission to build the remaining 35 turbines was deemed expired in 2024.

SERIOUS THREATS TO SPECIAL RESOURCES

The Whistling Ridge proposal was without question one of the most controversial, problematic, and environmentally consequential wind energy projects that has ever been proposed in Washington State.

The project would have harmed wildlife by permanently removing thousands of acres of forested habitat, including within a designated special emphasis area for the northern spotted owl, a state-endangered and federally threatened species. Multiple state and federally listed mammal and bird species would also have been affected by the project, including the western gray squirrel, northern goshawk, bald eagle, pileated woodpecker, and numerous migratory bird species. The project site also provides habitat for multiple species of bats. The site was never surveyed for birds during key migratory periods, and many of the wildlife surveys that were performed occurred more than 15 years ago, making them stale and outdated.

The project also threatened severe impacts to scenic, cultural, and recreational resources. The project site is within three miles of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, the Oregon Pioneer National Historic Trail, the Historic Columbia River Highway (designated as a National Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places, as well as a National Historic Landmark), and the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail.

The project was proposed along the boundary of the National Scenic Area. The immense, 430-foot-tall turbines would have loomed over the Gorge horizon and would have been visible for many miles in every direction. The project would have permanently altered the scenic landscape within the Columbia River Gorge and Cascade Range in an area that is visited by tourists from all over the world for its unique qualities, including dramatic mountain vistas, steep cliffs, pastoral lands, and the Columbia River. The project site is also surrounded by recreational resources in every direction on federal, state, and private lands.

By diminishing Gorge scenic resources, the project would also have harmed the local tourism economy and negatively affected property values in surrounding communities. In addition, it would have caused substantial traffic and road damage along local roads during construction.

During EFSEC’s original review of the project from 2009 to 2012, hundreds of written and oral comments were submitted regarding the project, and 86% of them opposed or expressed concerns about the project. These included multiple adverse comments from government agencies, including the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service, given the project’s potential impacts to scenic resources and cultural heritage.

A PROJECT OF MANY NAMES

Over the years, the proposed project went through several name changes and project reconfigurations. It was first dubbed the “SDS Underwood Wind Generation Project” in 2002, when PPM Energy, Inc. requested from the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) a 70-megawatt generation interconnection to BPA’s energy grid for a new wind energy project on land owned by S.D.S. Lumber Co., LLC (SDS) in southeast Skamania County.

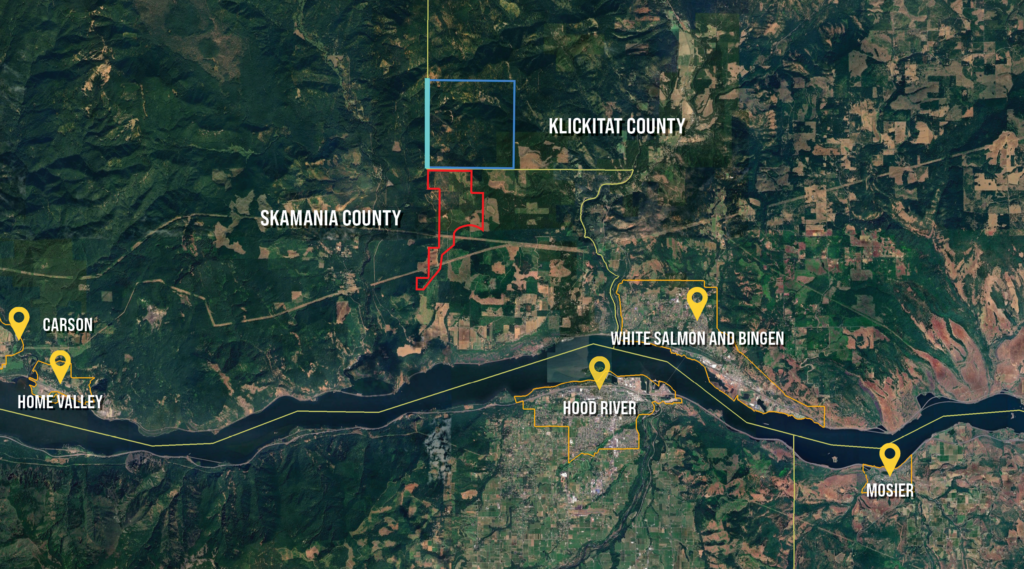

The project was not announced to the public, however, until 2007, when SDS proposed the renamed “Saddleback Mountain Wind Project,” which would have consisted of up to 85 industrial-scale wind turbines on prominent ridgelines, including Chemawa Hill, Saddleback Mountain, and Whistling Ridge. Fifty of the turbines would have been sited on private land in southeast Skamania County, and 35 turbines on public land (owned and managed by the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR)) in southwest Klickitat County.

By 2009, the project had been renamed yet again, this time to the “Whistling Ridge Energy Project.” That year, the newly created Whistling Ridge Energy, LLC (WRE), an SDS subsidiary, submitted an application to EFSEC for permission to build and operate 50 wind turbines on private land owned by SDS and Broughton Lumber.

POORLY DESIGNED PROJECT

Later in 2009, the DNR rejected SDS’s request to build 35 of the wind turbines on public land given the potential impacts to northern spotted owls and their habitat. Many of these turbines proposed on public land would have been built on the narrow Whistling Ridge—some of them literally on top of the Whistling Ridge Trail. Such construction would have forever obliterated a trail that is a source of great solitude and located off the beaten path, yet readily accessible from the central Gorge. DNR’s rejection of the 35 turbines on public land left the project proposal with just the 50 turbines planned on private land (none of which, despite the new project name, would have been located on Whistling Ridge).

In 2012, following a lengthy, complex adjudication and public comment process presided over by EFSEC, former Governor Gregoire denied permission to build 15 of the proposed turbines in order to reduce the project’s impacts to scenic, cultural, and natural resources. The governor, however, did grant permission to build the remaining 35 proposed turbines, each up to 430 feet tall.

Litigation ensued thereafter, including in the Thurston County Superior Court, Washington Supreme Court, and federal Ninth Circuit. Although none of the courts reversed the project approvals, the state supreme court did determine that additional project review was necessary and that several issues would need to be resolved by state officials, including impacts to migratory birds, wildlife mitigation, and review of the project’s clearcuts and other forest practices. In other words, the legal battles were far from over.

DEAD ON ARRIVAL

From the very day in 2012 when the governor rejected 15 and approved 35 of the Whistling Ridge wind turbines, project representatives began declaring the scaled-down project economically unviable and, for all intents and purposes, dead on arrival. In a statement to the media, WRE announced that the project was on hold and “unlikely to move forward.”

Indeed, over the ensuing decade, WRE never took any steps to move forward with the project—not even after all litigation involving the project was resolved. In November 2021, SDS transferred the project, the project site, and parent ownership of WRE to Twin Creeks Timber (TCT) and its affiliates without obtaining approval from EFSEC or even notifying the agency in advance about the transfer.

Then, in March 2022, the state-issued permit for the project, called a “site certification agreement” (SCA), expired by operation of law, 10 years after its issuance. The project was officially terminated. Or so we thought.

A FAILED RESURRECTION

Even though the SCA for the Whistling Ridge project expired in March 2022, TCT and WRE waited more than a year and a half after that point to submit two separate, formal requests to EFSEC. Like an attempted voodoo resurrection trick, one of the requests would have revived and extended the life of the expired permit. The other would have retroactively approved the transfer of the permit and the project to TCT as the new parent company. TCT and WRE explained that they were requesting all of this so they could consider whether to eventually build the project, but with even taller wind turbines than had been approved by Governor Gregoire more than a decade prior.

Friends and allies participated thoroughly in EFSEC’s proceedings for reviewing these two formal requests. We noted that the SCA had already expired, and that there was no authority for reviving or retroactively extending an SCA after its 10-year expiration date. We also submitted extensive testimony from expert witnesses explaining the many ways in which building this project—especially with taller turbines than were approved—would severely harm the environment and the public welfare.

Meanwhile, despite repeated requests by Friends, EFSEC staff declined to provide any notice of the pending requests to its official lists of more than 900 people known to be interested in the Whistling Ridge Energy Project. As a result, hundreds of people were completely in the dark about the proceedings.

In the end, EFSEC rejected both of the requests filed by WRE and TCT. In its written order, EFSEC explained that proposed new owner TCT had failed to demonstrate that it had the organizational, managerial, financial, and technical capabilities to build and operate the project as originally approved by Governor Gregoire in 2012. That was especially true given that TCT admitted it had little interest in complying with the governor’s restriction limiting the wind turbine height to 430 feet, but instead would like to pursue even taller turbines. EFSEC concluded that taller turbines would make this a different project, and if TCT wants to pursue a different project, then TCT will need to start over by submitting a new application for a permit.

In an important part of its written decision, EFSEC agreed with Friends and allies that the site certification agreement had “expired without [WRE] starting construction.” That ruling was vindicating, given that Friends had made this argument all along. The law in Washington gives energy developers 10 years after an SCA is issued to start construction of a project, which is more than enough time. Here, the chronic failures by the Whistling Ridge proponents to pursue the project became its very undoing.

It would seem unlikely that TCT (or anyone else) might ever propose a new industrial-scale wind energy project at this site. In addition to the many environmental and community impacts detailed above, the Whistling Ridge project site is also within a dedicated flight path utilized by the U.S. Navy, within which new development is limited to a ceiling of 500 feet tall in order to keep the airspace clear and safe for military training exercises. Every year, wind turbines are getting taller and taller to maximize efficiency and energy capacity; these days, 650 feet is a typical height sought by developers in Oregon and Washington. It is improbable that the U.S. Navy would consent to new obstructions (in the form of spinning wind turbine blades) intruding into the airspace.

EXPIRATION BEGETS INSPIRATION: LEVERAGING THE VICTORY

Sometimes bad projects go out not with a bang but a whimper. That was certainly the case with the Whistling Ridge Energy Project. After many years of heated opposition, EFSEC eventually agreed with Friends that the permit had quietly expired. Ultimately, through a series of victories over the course of 15 years, Friends succeeded in keeping the central Gorge free of industrial-scale wind turbines.

The successes and lessons from stopping the Whistling Ridge Energy Project can be leveraged elsewhere, and are already inspiring Friends’ ongoing legal work. Recently, Friends convinced the new owner-developers of the proposed Summit Ridge Wind Farm in Wasco County—which is controversial in its own right because it threatens many of the same types of resources as Whistling Ridge—to abandon their state-issued permit for that project, which had also expired. But the Summit Ridge developers have not completely given up, and have filed a notice of intent to seek a new permit for a redesigned project at the same site. Friends will remain closely involved in that energy siting process if and when the developers file a formal application.

In addition, the parcels containing the Whistling Ridge site are the last privately owned land in Skamania County that is completely unzoned—where any type of land use and development activities can occur with no zoning restrictions to protect communities and resources. Years ago, Friends filed litigation against Skamania County for its failure to zone these lands, and Friends prevailed in the Washington appellate courts on procedural issues in that litigation. Since Friends filed that case, all other privately owned lands countywide have been zoned except for the Whistling Ridge site—but only because of the limbo status of the wind energy project. Now that the project is officially terminated, Friends will reach out to Skamania County officials to begin the process of finally zoning these last remaining parcels.