August 20, 2024

The Columbia Gorge’s breathtaking beauty has long inspired awe and creativity. When Friends first crafted the title “Share the Wonder” for our current campaign over a year ago, we could hardly have imagined the the remarkable acts of support from our donors, partners, volunteers, and collaborators, all united by their joy for this wild and wondrous cherished landscape.

In this issue of Passages, we’re honored to feature the inspiring story of Brad Johnson, a longtime Friends member and visual artist whose deep connection to the Columbia Gorge has led to the creation of “Terra Cascadia,” a magnificent new animated LED installation at the PDX Airport. Brad’s art vividly brings the beauty of the Gorge to life for millions of travelers, and we’re so thankful that he will be giving a generous donation to Friends of the Columbia Gorge from his artist’s commission.

Deeply inspired by this unique blend of artistry and philanthropy that underscores Brad’s commitment to preserving and sharing the beauty of the Gorge, I am grateful for the opportunity to interview him about this remarkable project and his journey. Brad’s willingness to also donate his time and photos for this interview sets an inspiring example of how art and philanthropy can intertwine.

Read on as we delve into Brad’s creative process, his passion for the Gorge, the innovative techniques behind his installation, and the lasting impact of his incredible contribution. Through his art and philanthropy, Brad invites us all to appreciate and protect the spectacular, enchanting natural beauty of the Gorge.

Lori Warner

Director of Philanthropy

Can you give us a short summary of the project?

Yes! Three selected artists—Rebecca Mendez, Ivan McClellan, and myself—each created videos that cycle through huge LED screens at the PDX airport throughout the day, punctuated by computer-generated landscapes created by the Port’s agency dotdotdash. My work will be featured throughout October and November, then will reappear in rotation with the other two exhibitions indefinitely starting January 2025.

What inspired you to create the “Terra Cascadia” installation for the new PDX terminal?

When I was invited to submit a proposal for the media canvases at the new PDX Terminal, I was at work on the visuals for a classical music concert about the Ice Age Floods, sections of which featured the Columbia Gorge rendered through animated 3D point clouds which would be projected on large scrims (*publisher’s note: a scrim is a piece of cloth or canvas that appears opaque until lit from behind, used as a screen or backdrop in theater and art) between the performers and the audience. Using this technique to depict the natural world is something I have been passionate about for several years. All of a sudden, this new opportunity became a way to supersize everything I was doing: my canvas went from a 26’ wide scrim to two 128’ wide by 23’ high LED displays. The target audience went from 300-500 people watching a single one-hour concert to over 16 million people seeing these landscapes all day, every day for years! I was consumed by excitement for this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bring the region I love to life in the new terminal’s monumental canvases.

How did your personal connection to the Columbia Gorge influence the design and content of your installation?

For the two decades I lived in Portland, the Gorge was my most frequented destination for outdoor recreation, and for the last 10 years I’ve been living Trout Lake—it is a landscape I’ve always loved and have come to inhabit. I knew early on how I wanted to capture and depict the landscapes I would feature in the work, but I needed a structure to work within—some parameters to define the scope of what would be featured.

From where I lived and worked in Portland, looking toward the east was always the aspirational view with the volcanoes in the skyline, all the worlds to explore within them, and the Gorge as the conduit in. As the airport is situated at the gateway into these worlds, it seemed natural to me to limit the scope of my consideration to this region: from the tops of St. Helens, Adams, and Hood down to their convergence in the Columbia. One of my first inspirations for Terra Cascadia was John H. Williams’ 1912 book The Guardians of the Columbia: the ‘guardians’ are Mount Hood, Mount Adams, and Mount St. Helens and the contents of the book break down to The River, The Mountains, and The Forests—a structure that helped frame my curation of location.

What aspects of the Columbia Gorge were you most excited to feature, and why?

I’ve been excited to capture the features of the Gorge that collectively define what is most unique about this place, and for me, the most captivating aspect has been the geology. I love looking at landforms and thinking about how they were created: when you look at something like Beacon Rock it is beautiful and unusual, and then you start to wonder how it came to be. The Gorge is an epicenter of intersecting overlapping layers of geologic history: the Columbia River Flood Basalts, the volcanic Cascades, the massive Columbia and Ice Age Floods that cut through the strata to reveal the mysteries of deep time. The geologic landforms are the most captivating to me—they are the ruins and remnants of stories of how this place came to be. The Oregon writer Barry Lopez remarked in his book Horizon “all landscapes are on their way to becoming something else, with incremental slowness and terrifying speed.” There aren’t many places on earth where this is so overt and evident.

How did you select the specific scenes and locations from the Columbia Gorge for your installation?

My first impulse was to think of the displays at the airport as diorama windows into the greatest hits of the Gorge—portraits of the pantheon of places we all celebrate—but I took a different approach early on in the process guided by my personal experiences with place, the capture technology, and the architecture of the terminal.

Scenes that I had a personal connection to were more important than the notoriety of a landmark. What is most enduring to me about the region isn’t just the concentration of attractions we all know, but the many lesser-known places that are hard to get to, scenes we discover by chance, or views that we might never see without this technology. I wanted to capture the experience of being in a place, of observing it firsthand, and not just what it looked like at a particular moment, but what it looks like from the inside out.

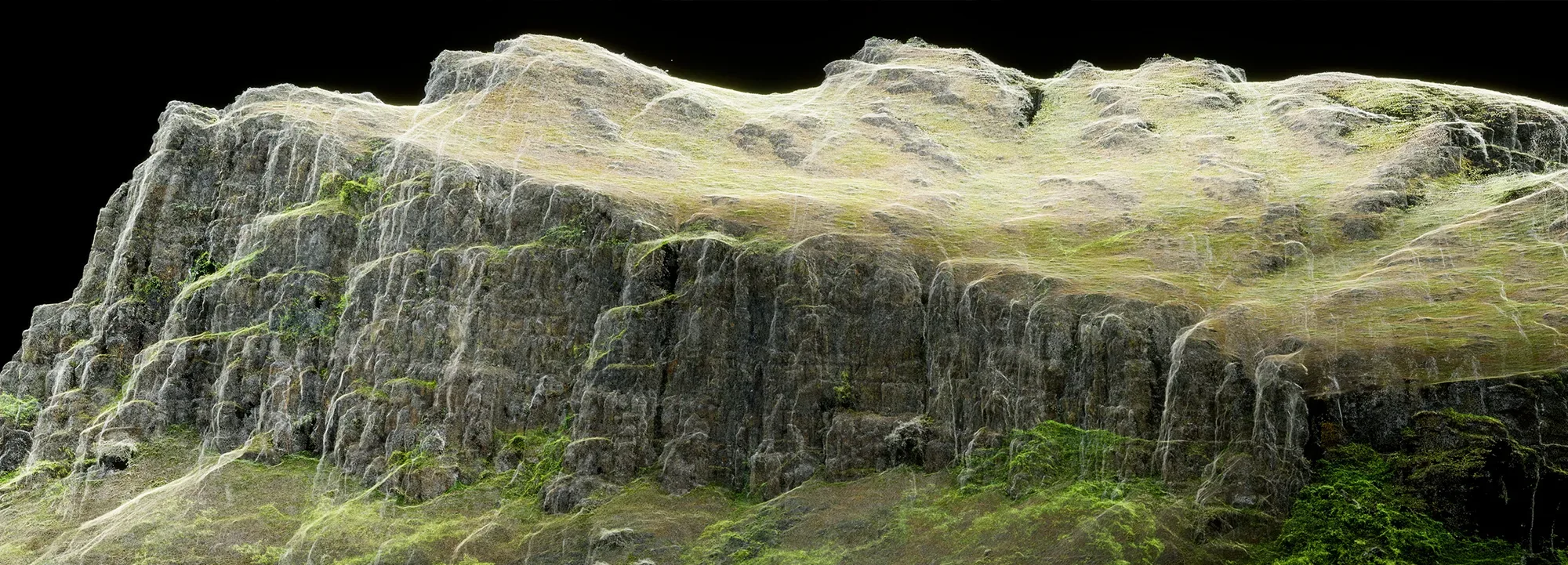

The technology I utilized lent itself to some scenes better than others. Rocks translate to point clouds better than vegetation and while forests are a defining part of the Gorge landscape, Zimmer Gunsul Frasca Architect’s design for the terminal is itself a kind of abstracted forest. This privileged my consideration for geologic features and views through the forest to defining landforms.

The severe wide-angle aspect ratio of the displays inherently served certain scenes better than others, and the north-south orientation of them inspired a story structure that helped focus what locations to feature. Rather than just playing the same scenes on both screens, I split the videos to feature locations from the Washington side of the Columbia on the north wall, and the Oregon side on the south wall. Both videos share the same rough sequencing: starting with portraits of the volcanoes as you might experience them when you fly out of PDX, the scenes cascade down from alpine glaciers through forests, streams, landforms, and waterfalls to converge along the Columbia. Since the structure and runtimes of the videos is the same, visitors can look across the terminal from one side to the other and see similar kinds of locations, but each is from their respective side of the Gorge. I came to be inspired by the native legends about Pahto and Wy’East competing for the affection of Loowit: here in the airport each mountain shows off their most endearing features from top to bottom.

What types of viewers or travelers are you targeting with your art installation, and why?

I thought of the audience being either people traveling from here or to here—residents or visitors—people who might have a strong connection to these special places and those unfamiliar. While I was first competing for the project, I was flying from Chicago to PDX and overheard a woman talking to her daughter at the O’Hare gate. They were excited that they would have window seats on the left side of the plane and would have a view of Mt. Hood. I thought about how captivating it is for all of us to fly right next to Hood, Adams, or St. Helens, to see them up close from many angles. I wanted to start the work with that experience, then fuel wonder about the worlds within and surrounding them. For visitors, it is an invitation into the unseen, and as my collaborator Thomas Wester said for residents, Terra Cascadia “welcomes us home before we leave.

What emotions or messages do you hope your art conveys to viewers at the airport?

What is most enchanting about working with 3D point clouds instead of photography or videography is the dream-like quality of its representation: things look very familiar, to varying degrees recognizable or literal, yet they have a quality that is not realistic. I love when I hear people come to recognize a scene, when it resolves from mystery to familiarity…sometimes after the fact. Maybe you’ll see Mist and Dalton Falls or St. Peter’s Dome in the video and they look familiar, but you aren’t sure why. Later you drive east on I-84 and pass these places to realize—like Dorothy at the end of Wizard of Oz recognizing her neighbors in the characters of her dream—“but it wasn’t a dream. It was a place! And you, and you, and you, and you were there!”

Can you explain the process of creating 3D point clouds from photographs and how this technique brings the scenes from the Gorge to life?

All the imagery in Terra Cascadia comes from 3D point clouds I created from over 10,000 photographs captured in the last five years from chartered airplane rides, drone flights, and dozens of hikes. For any given scene, I might capture between 30 to over 300 images with a high-resolution camera, a drone, or an iPhone. What makes the images good for this purpose isn’t what traditionally defines a great picture, but rather that I get comprehensive coverage of a scene from every possible angle. I then load the color-corrected images into a photogrammetry application that analyzes all the images and interpolates dimensionality from them. When the program sees the same feature from different perspectives and how it relates to neighboring features, it can extrapolate a 3D scene where every point is in fact a location in space with a color. Millions of these colored points together accurately represent the dimensionality and volume of a scene; where there is no data there is darkness, which is why the scenes are set against black.

The point clouds are then brought into a proprietary “virtual cinematography” application created by the Portland-based team of Thomas Wester, Ben Purdy, and Holly Newlands. This tool gives me the ability to fly customizable cameras through the scenes with a virtual reality headset, apply effects to the points, and render the animation to video. It’s like having the most powerful darkroom imaginable: I capture a scene in the real world, then bring it into this toolset to re-experience a place and reveal views that were never possible to witness otherwise. The software evolved as the project progressed and each scene is the result of a choreography between the data I captured and the tool’s capability. I couldn’t just decide to go capture a place and make a certain kind of animation, I had to find the best way for the location’s data to dance with the movement and effects at my disposal.

Do you see a role for public art to play in fostering a deeper connection between people and nature?

I like the landscape painter Casper David Freidrich’s notion that art is an intermediary between man and nature. The way an artist, writer, musician, or designer conjures the natural world expands how audiences think and feel about a place, the place becomes imbued with other associations, meaning or insight. In all my public art projects—whether material or digital—I have been focused on directly observing something in the natural world, capturing something about it to bring back to my studio where I could process it, respond to it, and create something that others could experience in a different (often urban) context. Hopefully this cultivates reverence for the natural world.

I once worked with Kent Weeks, the Egyptologist and founder of the Theban Mapping Project that mapped, documented, photographed, and archived the archeology of Thebes. He said, “preservation starts with documentation…if you don’t know what you have how would you know to preserve it?” That really resonates with me about art and nature. Ironically his project in 2001 was my first introduction to working with point clouds, and photogrammetry was mostly developed and utilized for documentation and preservation.

How did you collaborate with the team at PDX to integrate your installation into the new terminal design?

The Port of Portland and their partner dotdotdash had a very clear brief that set up the opportunity from the outset. They provided comprehensive material about ZGF’s awesome architectural vision, about the Port’s messaging and creative objectives, and about the technical considerations of the canvas. For me, the process was a lot like the scenographic collaborations I do with classical music performance: what I am making is one part of a multi-layered multimedia experience. In both cases, no one is coming just to see my work, but rather my work plays a part in an orchestrated whole.

Early on, dotdotdash created a VR application in which I could visualize my work-in-progress within a rendered 3D version of the terminal where I could navigate to any position and see what things would look like at different times of day, different lighting conditions, etc. Throughout the process, I was able to share my progress and at several points test preliminary versions onsite.

What were some of the challenges and rewards of working on such a large-scale project with two 128’-wide LED walls? (IOW, what was your initial reaction when you were given a canvas of two 120’ movie screens?)

The scale of these screens is awesome and was beyond anything I ever imagined working within. I’ve made large-scale public art installations and have done immersive scenography for 45th Parallel concerts on 26’ wide screens, but this is a different story altogether. It’s a rare opportunity to bring landscapes you love to life at such a scale, and from the moment I was awarded the project I was committed to make the most of it. Scale helps impart the presence of place, especially many of the monumental landforms featured in the work. That scale can be daunting however when movement comes into play: what might be a normal sweeping camera move on your large computer monitor can become overpowering or bewildering when it rips across 128 feet.

The creative challenge I faced throughout the project was maximizing the number of scenes I wanted to include with the minimum amount of movement required to show each one off. The beauty of working with point clouds is being able to see something from several different angles, to be able to see through the semi-transparent surfaces and behold its sculptural, volumetric properties. Scenes needed to be seen from a pivoting, orbiting, or tracking camera, and these movements take time: too much time on any one scene meant less scenes, but throughout the process working with the Port and their team at dotdotdash I got to experience different versions on site at different points in the process and ultimately featured over 60 scenes in 30 minutes of footage split between four videos.

How do you balance your artistic vision with the technical and practical aspects of working on a high-profile installation like this one?

I approached this project from the outset with a focus on making the best experience I could specifically for this installation. I would use similar media in different ways for different contexts. I have an obligation to the content and the audience. My goal is to be able to revisit any of the scenes I included and feel that what I find beautiful, sublime, or exceptional about them was served in what I made—to drive by Table Mountain when the sun rakes across the faces in the morning and say ‘I got that’…that I didn’t let Table Mountain down. Ultimately a project like this really isn’t about me, it’s about the 16 million people per year underneath the screens waiting to go through TSA—you have to craft something for that mindset. The screens are unavoidable and nearly impossible to ignore: there are only two ways to the gates and these portals are flanked by the screens. I had to tune what I made for that reception.

How did your artistic approach evolve throughout the project, and what did you learn from the process?

During the nine months I worked on this project, several aspects of my approach changed: the technology evolved, my awareness and observation of the Gorge was enhanced, and my facility with the tools was honed. Newer versions of the photogrammetry application were released enabling me to go back and redo old point clouds with more comprehensive data revealing parts of scenes that had been hidden. My technology colleagues Thomas Wester and Holly Newlands rebuilt the virtual cinematography tools to author specifically for the 128’ wide screens’ native resolution, increasing my point cloud resolution from 5 million to 256 million points. Their authoring controls became more powerful, and as the project progressed I was empowered to do things I hadn’t been able to before.

A huge lift came when the Port changed the opening from early May to August. I was originally limited to capturing the scenes I could from November to March or April—tough seasons to access some of the best locations in the Gorge, and ultimately a limited representation of the full spectrum of how it is experienced. The extension let me capture many more locations in different seasons. I ultimately became much more connected to the Gorge—how all the discreet locations were connected—to see recurring motifs and themes throughout the region, and learned to appreciate how places change throughout the year.

How do you envision travelers experiencing and interacting with your art as they pass through the airport?

I hope people look up and feel transported, that they lose themselves in the scenes, that they are enchanted.

Can you share any feedback or reactions you’ve received from people who have seen the installation during the airport’s soft opening or previews?

Some of the words I have heard from people: mesmerizing, enchanting, dream-like, magical realism, sublime, mysterious, awesome, awe-inspiring, mind-blowing, total-Rivendell, atmospheric, relaxing, refreshing. People say they feel like they are on a journey, like they’ve been on a ride, like they are discovering things. People always want to know where everything is…what is that place? They seem to respond to the sequences where something is enigmatic, then it resolves somehow and they understand what they are looking at, from mystery to familiarity.

What impact do you think this high-profile installation will have on the visibility of the Columbia Gorge and environmental awareness?

The Gorge is one of the region’s most cherished natural resources, and to me it is the keystone element of our natural heritage. I hope this installation helps contribute to our community’s valuation and stewardship of the Columbia Gorge.

How do you think showcasing the Columbia Gorge in an international airport setting might impact viewers’ perceptions of the region?

Hopefully it will encourage pride in living in such a spectacular place, inspire curiosity to visit and explore what it has to offer, and cultivate wonder these landscapes exude.

What are your future projects or goals, and do you have any plans to integrate environmental themes into them?

I am working on a longer-term project about the Ice Age Floods that is both in exhibition format and in a concert series with 45th Parallel. As the last ice age ended, 7 million square miles of melting glacial ice unleashed cataclysmic floods that raised sea levels nearly 400 feet. The planet was transfigured, human settlements were submerged, and flood myths were imprinted in cultures around the world. The floodscapes in Washington and Oregon are perhaps the best-preserved evidence on earth that documents this dramatic change of climate, and this project surveys our storied landscape through art and music.

The Floods will be a mixed media art exhibition with a companion visual music concert exploring the cataclysms that sculpted landscapes from Montana to the Pacific through Washington and the Columbia River Gorge. A musical program of adapted, rearranged and original contemporary classical compositions will be performed within large-scale projection scrims visualizing the landforms, legends, and forces of nature that defined our region and heralded a new epoch of the planet.

Can you share any memorable moments or insights from working on this project that stood out to you?

This project has truly been a career-creative-life honor to be part of. It drew on the experience of my 20-plus year career with Second Story, the Portland-based interactive media studio I co-founded with my wife and creative partner Julie Beeler who produced Terra Cascadia. I got to collaborate with Thomas Wester, Martha Almy, and others I worked with at Second Story over a decade ago, something I never imagined happening again. It drew on my ongoing observation and documentation of the Gorge and my art practice, and it provided the most unbelievable canvas on which these things could converge, in a venue of spectacular beauty with more eyeballs on it than everything I have ever done combined, times 10!

To experience and observe a place that means a great deal to you, then capture what is most remarkable about it with technology that helps reveal the inherent beauty of a place, then share it with millions of people that are passing through here, with this amazing seductive display, it has been a dream to be part of this.

What do you hope the donation to Friends of the Columbia Gorge will achieve, both for the organization and for the preservation of the Gorge?

My wife Julie Beeler and I have been giving to the Friends of the Gorge for many years—it is an organization that preserves and protects something we care deeply about. After focusing this project on the Gorge I decided to give part of my commission to the Friends. The Gorge has given a lot to me for much of my life and I am happy to give back.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Brad for his time and insights with us.

As we celebrate the debut of “Terra Cascadia” in the new airport terminal, we eagerly anticipate the impact this extraordinary installation will have on travelers and its role in inspiring Gorge wonder. Stay tuned for updates on how this breathtaking project continues to resonate with those who pass through the airport and its influence on our shared appreciation of the Gorge.