By Kevin Gorman

Executive Director

February 2, 2024

Twenty years ago today on Groundhog Day, Friends of the Columbia Gorge learned that Gorge conservationist Norman Yeon had included a $4.5 million bequest to Friends in his will. Below, Friends Executive Director Kevin Gorman tells the behind-the-scenes story of the most transformational gift in the history of our organization.

For many, Groundhog Day is a movie that became a cultural déjà vu meme or an obscure holiday focused on rodent meteorologists. For me, Groundhog Day is the day that changed Friends of the Columbia Gorge forever.

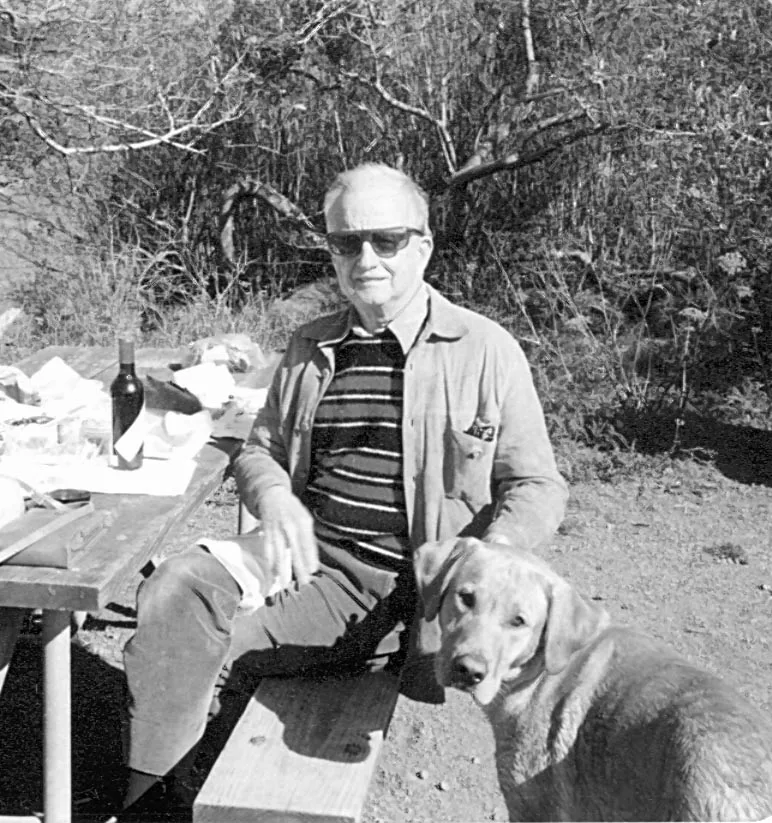

On Groundhog Day 20 years ago, I was a little more than five years into my job as executive director of Friends of the Columbia Gorge. The organization was taking on bigger challenges and our Founder Nancy Russell was finding a groove with our then-Development Director Jane Harris as they became a fundraising tandem. Jane was interested in expanding our planned giving efforts and asked Nancy to reach out to longtime donors, including Norman Yeon. In our minds, Norman lived in rarefied air. His father was John B. Yeon, the builder of the Historic Columbia River Highway, and his brother, the younger John Yeon, recruited Nancy to start Friends of the Columbia Gorge in 1980, which eventually led to the creation of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. But over the years, Friends had had very little contact with Norman though Nancy knew him in passing.

Nancy and Jane visited Norman on his coastal property in 2003 and when Nancy asked Norman to consider leaving Friends in his will, Norman listened and then quietly said, “I’ll think about it.” Nancy and Jane left Norman not knowing what he would do. Later that year, Norman passed away and it was on Groundhog Day 2004 that a package from a San Francisco law firm showed up in our mail. Jane Harris brought the large envelope to my office and said, “I think this is Norman’s estate.” We moved to her office, closed the door, and began reviewing his last will and testament. It’s unusual for a nonprofit to receive an entire will but this one laid out Norman’s values and hopes for the future. The will had been changed and updated six months previously (maybe due to their visit?) and the bulk of his estate was directed to three nonprofits: Reed College, Trust for Public Land, and Friends of the Columbia Gorge. As we read numbers and percentages, we tried to answer the question both of us had: What would Friends receive? It quickly became clear that Friends would receive an unrestricted bequest of over $4 million, about seven times our annual budget at the time.

The two of us sat in stunned silence. We knew the first call we needed to make was to Nancy Russell. Nancy listened as we shared the news, and after several seconds of silence from her, she said “I can’t feel my legs.” We laughed as the astonishment and relief in her voice said everything. Less than a decade earlier, Nancy was writing checks to cover staff payroll and hanging on for dear life working to ensure the nonprofit she founded would outlive her. Now she knew that it would not only survive, but perhaps thrive.

Our elation was short-lived. Within a few weeks, Nancy shared with me that she had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive neurodegenerative disease that is typically fatal within four years of diagnosis. Urgency pushed away grief and excitement as both Nancy and I knew exactly what the organization needed to do with those funds: launch a land trust.

Nancy had been a conservation buyer in the Gorge for years, purchasing land to stop development or sometimes buying developed land and removing the development. She had purchased more than two dozen properties, resold and donated a few to government agencies, and kept the rest.

Six months before that fateful Groundhog Day, Nancy had brought up with me the issue of her lands and what should become of them upon her death. We discussed a number of scenarios but ultimately agreed the best place for them would be with Friends of the Columbia Gorge. But at the time, Friends did not have a land trust program and it was extremely rare for a conservation advocacy organization to engage in land acquisition. Nevertheless, Nancy said she planned to leave the lands to Friends, in addition to some funds for the organization to create a land trust. That sounded fine with me as I was convinced I would never have to deal with that. Nancy was in her early 70s, the picture of health—prior to her ALS diagnosis, I envisioned her living into her 90s and beyond. I was certain that starting a land trust would be a job for a future executive director.

The Yeon bequest, coupled with Nancy’s diagnosis and our conversation about her land holdings, thrust Friends into an 18-month planning process to create a new entity, Friends of the Columbia Gorge Land Trust. We hired our first land trust employee, Kate McBride, and got to work fast. Within seven months of incorporation, we purchased our first property, a four-acre private inholding surrounded by hundreds of acres of public land. The property is now the site of the Nancy Russell Overlook along the Cape Horn Trail. A beautiful natural area, the casual observer would never know the property was once a gated residence with a 5,500-square-foot house and four-car garage. Friends removed all the development, sold the bare land to the U.S. Forest Service, and paid for the basalt overlook that is now enjoyed by thousands of people every year.

In the 20 years since Groundhog Day 2004, our land trust has acquired 43 properties totaling 1,775 acres. We’ve preserved wildflower meadows and old-growth forests. We’ve saved turtle ponds and pika habitat. One acquisition, Steigerwald Shores, helped unleash the largest salmon restoration project in the history of the lower Columbia. We’ve built trails and added bilingual signage. We stopped multi-million-dollar mansions from taking over beautiful, undisturbed plateaus. And in cases like Cape Horn and now at Catherine Creek, developed landscapes are being restored to their natural origins. Norman Yeon’s gift was never intended to start a land trust, but I feel confident he would have been thrilled with how we put his gift to work.

Groundhog Day may be just another day for you. But for me, it represents possibilities, new beginnings, and hope for the future.