by Hannah Anderson-Dana, Member & Public Engagement Specialist

The Northwestern pond turtle has survived for more than 200 million years, yet in the Columbia Gorge today its future is perilously uncertain. Habitat loss, disease, and—most critically—the explosive spread of invasive American bullfrogs have pushed this ancient reptile to the brink. Protecting it is work that can’t slow for even a season; recovery depends on steady monitoring, habitat restoration, and the persistence of people committed to giving this species a fighting chance.

At Friends’ Turtle Haven and Alashík preserves, that commitment is unfolding pond by pond. These protected landscapes—once degraded and fragmented—now serve as vital strongholds where biologists track turtles, restore wetlands, and search for individuals across a connected network of ponds. This article takes a closer look at that work: how decades of field science, cross-agency partnerships, and careful stewardship are helping rebuild one of the Gorge’s most vulnerable native populations—and why the future of the species may well hinge on places like these.

On a rainy Friday in June, I drove out to Friends’ Turtle Haven preserve to meet with Carly Wickhem and Matt Monteith, wildlife biologists from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), who were on the property to conduct population surveys of the endangered Northwestern pond turtle. I looked on as they set turtle traps in the ponds which, once installed, stay in place for three weeks while biologists check them daily to identify and tag any trapped turtles.

This strategy plays out at 64-acre Turtle Haven, which Friends purchased in Skamania County, Washington, in 2015 as part of our Preserve the Wonder capital campaign, to protect the Northwestern pond turtle and its habitat. For many years, Turtle Haven was surrounded by hundreds of acres of U.S. Forest Service land, all speckled with small ponds and inviting to the pond turtle. Given that turtles don’t understand property boundaries and can move up to three miles overland, having access to the land around their habitats is crucial to monitoring and boosting the populations. When Friends purchased the 120-acre Alashík Preserve in 2024, wildlife biologists are now able to explore its many ponds to find even more turtles.

On these properties, which are closed to the public, you get the feeling of a return to the wild—aside from the biologists’ stowed kayak for getting out on the pond and their materials to tag the turtles, you can’t see any structures or our cars parked on the adjacent road. No signs of human interference. A reminder that this place isn’t ours; we just play a role in this ecosystem that was here before us and will continue on long after us.

It’s a thrill being here—to see and feel the scope and impact of the work—but this feeling was not always palpable at Turtle Haven. On my first visit back in 2021, dilapidated structures, rusting cars, and piles of unidentifiable materials dominated the landscape. Now four years later, it’s incredible to see the tangible effects of Friends’ work restoring habitat and giving the turtles and other wildlife on these properties space to roam. Watch a before-and-after video of our restoration work at Turtle Haven here.

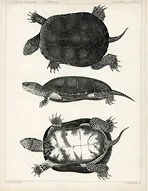

I’m excited to be getting a behind-the-scenes look at this work at Turtle Haven. But first: counting turtles. I try not to focus on how wet my socks are and zero in on the beautiful markings of the male Northwestern pond turtle Matt has just handed Carly. For a species that has survived for over 200 million years and outlived the dinosaurs, it’s sobering that their greatest threat, and the thing most likely to bring their eons of existence as a species to a close, is human impact.

The Northwestern pond turtle used to range from British Columbia to Baja California, an expanse of over 1,400 miles. But loss of habitat from development—like the construction of railroads, highways, and dams—and the draining of wetlands for urban and agricultural development had such a drastic effect on the population that when WDFW went looking for turtle populations in the 1980s in Washington state, they found just two groups–a population in the Puget Sound area and one in the Columbia Gorge—totaling 150 turtles.

While tracking and marking turtles within those populations, WDFW scientists made an ominous discovery: many of the turtles were sick and malnourished. Too weak to submerge, they faced an existential threat—a species that can only feed underwater cannot survive exclusively on land. The sick turtles were brought to the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, where just 15 of the 40 females survived.

Once strong enough to be released to the Sondino Ponds outside of Lyle, Washington, WDFW hired Kate Slavens, who, along with her husband Frank—the then-reptile curator at the zoo—was instrumental in starting the turtle conservation program. Kate and Frank would drive 500 miles round-trip to monitor the surviving turtles.

During this monitoring period, six turtle nests were found. Those babies were taken to a former pheasant holding facility in South Puget Sound to grow big enough to survive at the zoo and then on their own.

This process, known as “headstarting,” involves placing a transmitter on female turtles in April, searching for and finding their nests through July, and coming back in September to dig up the nests. The baby turtles are then reared in captivity for the first 10 months of life until they’re large enough to defend themselves against predation by bullfrogs—when they’re too small, baby turtles make prime snacks for bullfrogs, since they can’t swim well enough to escape and are tiny enough to swallow.

This process continued for some time—track the female turtles, find their nests, and dig up the hatchlings to rear for 10 months. Turtle release sites expanded to two in Puget Sound and four in the Gorge. The Oregon Zoo got involved in 1998 with headstarting turtles and Friends started releasing turtles on our properties in 2019.

As the years went on, those involved in turtle conservation learned more about how best to protect these reptiles. It quickly became apparent that the American bullfrog, North America’s largest frog, was the turtle’s biggest threat. Kate and Frank would walk around the Sondino ponds and count upwards of 100 bullfrogs, waiting for a tasty turtle snack.

In order to have the turtles reach the stage where they can hatch eggs that succeed and survive (also known as recruitment), they would need to manage the bullfrog problem.

They started by removing bullfrogs they could see, capturing hundreds at a time (and these bullfrogs can be huge!). But they quickly shifted the focus to all life stages, as an attempt to eradicate the problem from the beginning by removing bullfrog egg masses from the ponds.

Bullfrogs present a tricky issue. Hatched bullfrog eggs in a pond can set a turtle population back three to five years, since a female American bullfrog lays thousands of eggs (between 5,000 and 20,000). WDFW District Wildlife Biologist Stefanie Bergh alluded to this added challenge at these particular sites because it’s not just bullfrogs staying in the borders of one site: they can hop across properties from pond to pond and ignore the boundaries of land ownership. They also end up in places biologists haven’t gone to yet to scout turtles and bullfrogs.

In the coming years, bullfrog removal will continue to be a priority for turtle conservation, along with learning more about the shell disease that’s affecting mostly the headstarted turtles, and managing effects from climate change-related drought on the turtles’ ponds.

For this piece, I spoke with Matthew Bettelheim, a wildlife research biologist whose work documents the Northwestern pond turtle populations in California. Matthew remains optimistic about protecting the species, given the proven resiliency of the turtles. He says that witnessing the community of passionate, curious, and determined conservationists and turtle enthusiasts working together for more than 30 years is a great sign that this work can go far (and already has!).

A fun and frustrating part of turtle conservation, Matthew says, is that “every time we thought we learned something new, we had five more questions to ask.” Stefanie from WDFW echoed that sentiment, that new knowledge about the turtles “keeps us on our toes.” Frank and Kate Slaven were motivated by the continued success year after year—going from 150 in the 1980s to over 800 at the last count—and the ongoing opportunities to learn more about the turtles, like observing how they make their “perfect nests, shaped like upside-down lightbulbs.”

Something that I keep returning to is the longevity of this problem-solving and the commitment from so many different people to play a part: Kate driving 500 miles round-trip to count turtles, the biologists at WDFW going out to sites every day for weeks, the Columbia Gorge Museum in Stevenson, WA, devoting an entire exhibit, “Illustrating Ecosystems: Native Turtles and Plants of the Gorge” to the history of this conservation (the new exhibit is now open indefinitely).

This exhibit and my interview with Morganne Pockels, the then-Collections Manager at the Museum, was my introduction to Frank and Kate’s work and planted the seed of exploring the many moving parts and partnerships of turtle observation and conservation over the past century and the role this small species plays in our ecosystem. The exhibit displays not only turtle specimens (I recommend going if you want to see how many baby turtles a bullfrog can fit in their mouth) but also railroad survey illustrations from the 1850s and preserved plant samples.

Sara Woods, Friends’ Stewardship Manager, highlighted the uniqueness and power of this partnership work with multiple organizations and agencies, as it pulls together different breadths of knowledge, funding, and capacity. It displays the strength of like-minded organizations with similar goals doing great work.

But learning never stops. This collaboration shows what focused partnerships can achieve for a single species and its habitat. Visiting Turtle Haven, I’m reminded of the legacy that collective effort leaves behind—and that even though we may see ourselves as separate from the ecosystem, our impact is undeniable.