by Sara Woods, Stewardship Manager

Invasive American bullfrogs have devastated populations of the endangered Northwestern pond turtle for decades, swallowing hatchlings whole and reproducing with exponential speed. By 1990, only two populations of turtles remained in Washington. Since then, Friends and multiple agency and zoo partners have worked together to “headstart” more than 1,800 turtles, with about 95 percent surviving their first year. It’s a battle that can’t stop, even for a season. If it does, bullfrog populations rebound and years of progress unravel.

Bullfrog management in the Gorge moves with the rhythms of the year: winter planning, spring egg-mass searches, and summer and fall nights removing adult frogs. With this article, we begin a three-part series tracing how this work unfolds seasonally. This chapter focuses on winter work, when bullfrogs slow into dormancy and we shift to planning, data review, and preparing crews for the coming field season. In spring 2026, we’ll highlight early-season fieldwork.

Friends and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) co-manage bullfrog control efforts on our respective lands in coordination with Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). Since we started this work, we’ve removed over 16,500 bullfrogs and 200 egg masses out of 32 ponds on USFS lands and Friends’ Alashik and Turtle Haven preserves. Of course, bullfrogs do not abide by the human-created concept of legal boundaries, and therefore, cross-boundary stewardship is critical to their management. This cooperation ensures our efforts are efficient and that we are not leaving any pond lily unturned, but it comes with a hefty price tag.

Each partner contributes in different ways, like land access, night field crews, and data analysis, and success depends on aligning these pieces each year.

Bullfrog Problems

Bullfrogs are a “gape-limited” ambush predator, meaning they eat anything that can fit into their open mouths and swallow their prey whole. Their diet consists of invertebrates, birds, bats, rodents, frogs (including bullfrogs), newts, lizards, snakes, and turtles. They are also known to be vectors for diseases such as Ranavirus and Chytridiomycosis that can infect and kill native frogs such as the Oregon spotted frog and the northern leopard frog. Bullfrogs also reproduce on an exponential scale that outcompetes their native counterparts.

Through our collaborative culling work, bullfrog stomach contents were analyzed and unveiled a variety of native species they had eaten. At another Gorge site, one bullfrog’s stomach included two quarter-sized pond turtles. In Washington state bullfrogs are classified as prohibited aquatic animal species (WAC 220-12-090) due to the high risk of them becoming an invasive species to new sites.

Identification

American bullfrogs are stout frogs and adults have been documented to grow up to eight inches in length and weigh over two pounds (that’s one third the weight of the average human baby). They have long, hind legs and fully webbed hind feet. Their skin is smooth, and the color on their topside is typically tan, brown or olive-brown with varying amounts of black mottling, and their underside is a light cream color with dark mottling. Females have bigger bodies than males however the most distinguishing feature between sexes is their tympanum (or eardrum; located just behind their eye).

Female’s tympanum is approximately the same size as their eye, where in males it’s larger in size. The tympanum in males is critical to discern calls from other frogs to attract mates and defend territories. Males emit a loud, deep mating call that sounds like “jug-o’-rum” and “br-rum.” Listen to a sample here.

Range

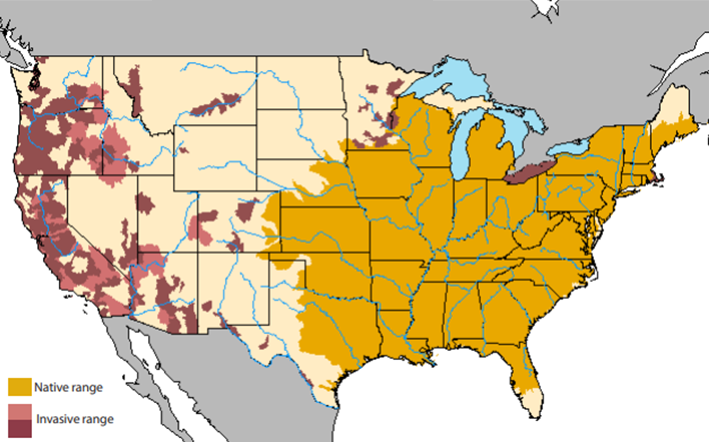

Bullfrogs are native to the central and eastern United States (U.S.), southeastern Canada, and have been introduced into the western U.S. in the early 1900s. They were introduced to the West for aquaculture (or frog farming) for food production i.e., frog legs. To a lesser extent, they were brought in as a biological control for insects and were released into natural waterways as unwanted pets. Bullfrogs presumably escaped farming operations and spread to natural areas, likely finding that the Northwest is quite hospitable with our mild winters and plentiful water features.

Habitats

Bullfrog habitats include ponds, wetlands, lakes, creeks, sloughs, and rivers. They generally stick to the shores of ponds and prefer areas with warm water and abundant aquatic vegetation. Hunting, breeding, and overwintering all occur in these same types of habitats, but they periodically move over land. Adult males hold territories along the water edges and physically wrestle unwanted males out.

Life Cycle

Bullfrogs go through a metamorphosis that includes multiple life stages: egg, hatchling, tadpole, juvenile, and finally adult. It can take 2 to 3 years of growth as a tadpole before they become a mature frog that’s able to breed. Mating occurs in the spring and females lay up to 20,000 eggs in a temporarily floating egg mass in June and July. More on this in the next issue of Passages in spring 2026.

Bullfrogs typically stay close to where they were born (1-2 km) and don’t technically migrate, yet young frogs do disperse to new habitats partially to evade cannibalistic adults. Dispersal occurs, en masse, on rainy nights. This behavior provides an opportunity to capture frogs out of water, if timed correctly, yet most bullfrog control efforts happen in a kayak, on the water, at night, with a spotlight and net.

Bullfrogs reproduce rapidly, disperse easily, and can reinvade sites quickly, which means effective control only works when it’s sustained over many years without a pause.

Winter

In winter, bullfrogs are underwater, burrowed into the muddy bottoms of ponds and slow-moving streams. They enter a semi-dormant, lethargic state called “brumation,” where they slow down their metabolic rate as ectotherms (from the Greek words “ektós,” meaning “outside,” and “thermós,” meaning “heat”) to retain energy due to the cold and the lack of food. They don’t fully burrow in the mud, as they need a portion of their skin exposed to absorb dissolved oxygen in the water to breathe. On warmer winter days, bullfrogs can snap out of their catatonic state and sluggishly swim around to feed. Managing an invasive species at this scale involves more than field time. It’s a continuous cycle of planning, adaptation, and preparation for the next season.

This time of year, staff from Friends, USFS, WDFW, and Mt. Adams Resource Stewards (MARS; responsible for adult night culling) are discussing the past bullfrog control season and sharing data, highlighting things we’ve learned and discussing how to improve our work through adaptive management. With limited resources, we are using our results and writing grant applications to hire field crews to continue the efforts for the coming season.

Funding this work is critical as we have come so far with our efforts. If this work paused even for a season, bullfrog numbers would rebound quickly, undoing years of progress and further pressuring native turtles.

This collaboration has been synergistic in the true sense of its meaning; our partnership is greater than the sum of our individual efforts, and we need each other as we bring different expertise and skills. We also need your support to get the work done, so thank you for your time, likes on social media, and donations.