Most all sites mentioned below can be found on our Find a Hike webpage for the hike description, driving directions, map, and more.

Wildlife Wonders

Wildlife Wonders

The Columbia Gorge is home to both easy-to-spot and elusive wildlife. You may never see the bobcat that watches you hike along a trail, but if you look up, it’s not uncommon to see bald eagles soaring overhead. Some animals, like the Larch Mountain salamander, are endemic to the Gorge—found nowhere else on the planet. Some, like the pika, migrate from alpine areas into the Gorge in summer. Its cheerful chirp might be the soundtrack for your hike across a talus slope. Here are three iconic Gorge animals that are easy to find while you’re hiking or exploring:

Banana Slug

Banana slugs are the stars of the slug universe: big and showy, sometimes spotted like a ripe banana, sometimes shining a solid brown yellow on the trail. Detritovores, they are possibly the greenest of all recycling organisms, eating leaves, animal droppings, moss, mushrooms and dead plants. Without them, our lush forests would be messy places. When you see one on a trail, think of it as a small vacuum cleaner, keeping the trail floor tidy.If you lick a slug you’ll understand why their predators roll them in dirt before eating them, to bind up the slime. Raccoons, garter snakes, geese, ducks and salamanders eat banana slugs. They have been eaten by humans, too, but probably only as a food of last resort. Find them on your favorite trail anywhere on the west side of the Cascades.

Osprey

Osprey overhead are a common sight in the Gorge: white feathers below, dark feathers above, with a white head. They can live 25 years and build huge stick nests, often on human-made structures near the water. Before humans came along, they used live or dead trees with flat, broken tops. A breeding pair will often return to the same nest year after year.

One little known fact about osprey is that they smell pretty bad. The odor is not from their all-fish diet but from the oil osprey secrete to keep their feathers waterproof. They dive to about 18 inches below the surface when they fish.

Osprey historically have left the Gorge in winter, though in recent years more are wintering over. Some Oregon birds have been tracked as far south as Honduras.

Sea Lion

Sea lions used to be uncommon in the Columbia Gorge, but in recent decades, male California (Zalophus californianus) and Steller (Eumetopias jubatus) sea lions have swum up the Columbia in the winter and spring to Bonneville Dam, 146 miles from the Pacific Ocean. Annual counts there range from 82 to 166 animals.

Find them this spring below the dam. Good viewing in Washington is along Dam Access Road, off SR 14 east of North Bonneville. In Oregon, you may spot them at the lock and dam site, at the mouth of Tanner Creek and on the north side of Robins Island, above the restroom symbol. View Bonneville Lock & Dam Map

My wonder

Which animal in the Gorge fills you with wonder? Where and what time of day have you seen it? #preservethewonder

Scenic Wonders

Scenic Wonders

It’s fun to take visitors to the postcard-perfect views at magnificent Crown Point. Here are three other just-as-spectacular spots—and with far fewer visitors. They’ll lift you from the Gorge floor up to its heights, to epic views. Make sure your phone or camera has a good charge!

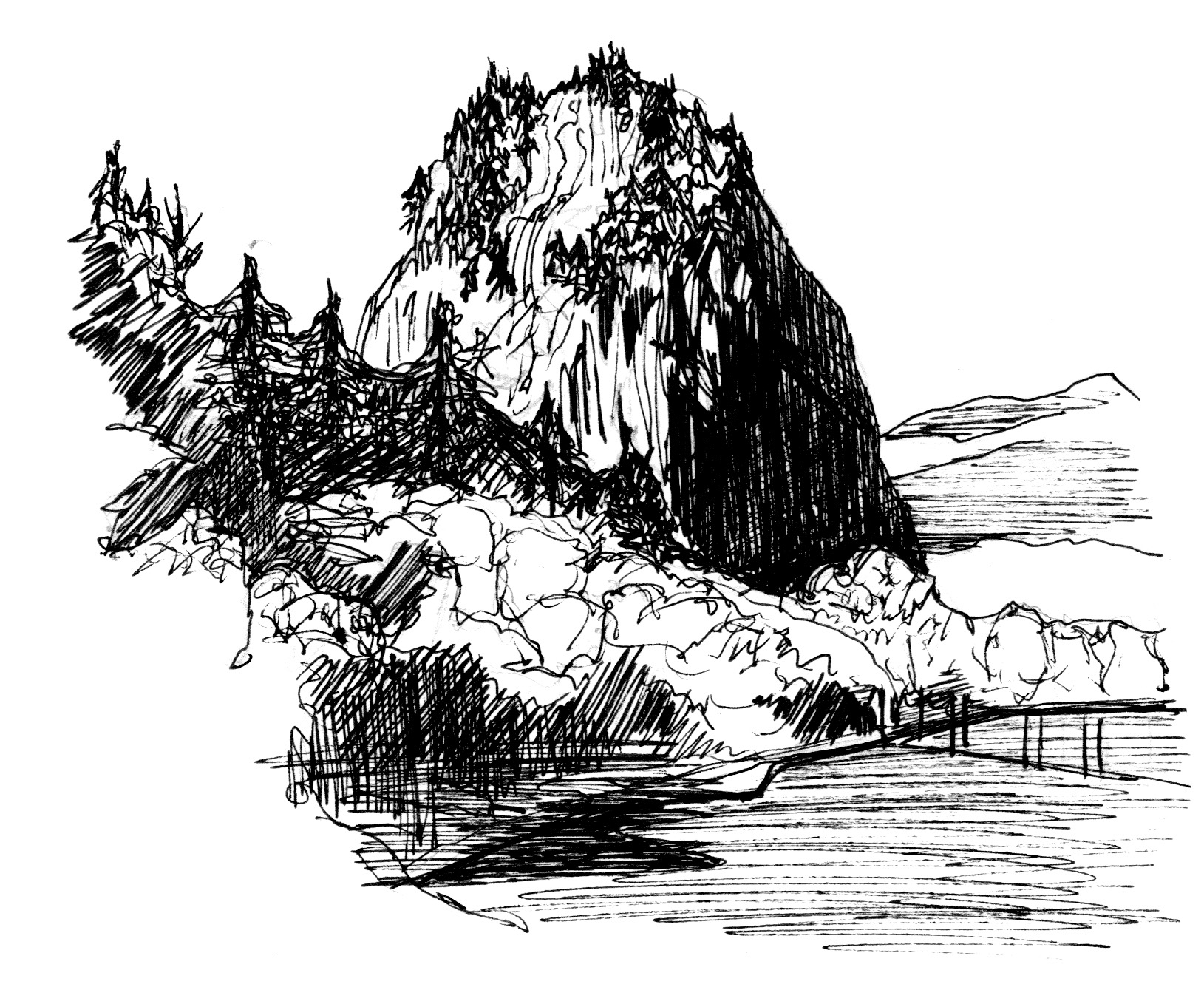

Beacon Rock

This 848-foot high column of basalt was once thought to be the core of an ancient volcano. However, geologists now think it is more likely a segment of a north-south running dike, lava that oozed up through cracks in the earth's crust 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. In either case, less resistant outer layers of rock were scoured away by massive floods during the last Ice Age, leaving the monolith we climb today. Cliffs on the rock’s south face testify to the power of floods that sheered them vertical. See this side from the boat landing at Beacon Rock State Park. Then climb to the top from the trailhead off SR 14. During the Ice Age floods, even at the top of Beacon Rock, you still would have been under water.

In 1904, Charles Ladd, son of Portland’s famous William Ladd (of Ladd’s Addition and other real estate fame) purchased the rock after hearing that some investors were considering acquiring for a quarry. In 1915, Ladd sold Beacon Rock for $1 to Henry J. Biddle on condition it would be preserved. Biddle wrote in 1924, “My purpose in acquiring the property was simply and wholly that I might build a trail to its summit.” (Climbers had climbed it with ropes in 1901.) He completed the trail in 1918. The route was later improved during the Great Depression by young men working for the Civilian Conservation Corps. In 1935, Biddle's heirs offered Beacon Rock to the State of Washington as a state park. Washington declined the offer, but later said “yes” after the same offer was accepted by Oregon. Thus, Beacon Rock very nearly became an Oregon State Park!

Nancy Russell Overlook

Atop the vertical cliffs of Washington’s Cape Horn, a 16-lot subdivision was planned in the early 1980s. This was a few years before Gorge protections were put in place by the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act. To prevent the development, Friends' founder Nancy Russell and her husband Bruce took out a bank loan in 1983 and made a no-interest loan to the Trust for Public Land. With the funds, TPL bought 12 of the lots. After the land became part of the National Scenic Area, the U.S. Forest Service bought the land from TPL. In 2001, Columbia Land Trust purchased two more properties, and in 2004 a few locals and avid trail advocates began exploring a possible loop trail.

In 2006, Friends of the Columbia Gorge Land Trust purchased the subdivision's one developed lot. Two years later a home and barn on that lot were deconstructed. The land trust also secured an option to purchase the last privately held property in the subdivision. Friends' Campaign for Cape Horn raised more than $4 million to secure the properties and build a public overlook that honors Nancy Russell.

Because of Nancy's vision, every Pacific Northwest resident, and every visitor from anywhere on the planet can enjoy this spectacular setting. Stand atop the Nancy Russell Overlook, dedicated in 2011, for one of the most awe-inspiring views in the Gorge.

Rowena Plateau Overlook

In the Eastern Gorge is a counterpoint to Crown Point: another clifftop, panoramic overlook on the Historic Columbia River Highway. Here in the arid land east of the Cascades, the ground was stripped bare by the Ice Age Floods. From the top of the plateau, the Gorge’s geologic story is on full naked display: layers of basalt flows, side canyons widened by the raging floods, and kolk ponds—depressions scoured out by the floods. In spring, the thin soils of the plateau bring forth a wildflower show you won’t want to miss.

You can't talk about the Rowena Plateau without talking about Tom McCall Preserve at Rowena, a Nature Conservancy site. Each spring, volunteer docents lead interpretive hikes.

My wonder:

Which Gorge viewpoint or vista fills you with awe? What are its special features? #preservethewonder

Wildflower Wonders

Wildflower Wonders

More than 800 types of wildflowers bloom in the Gorge, 15 species of which grow here, and nowhere else on earth. Some, like the oddly named grass widow, can bloom as early as late January (though not this year!). April and May are the big color months, with balsamroot and lupine carpeting slopes in the Eastern Gorge. Blooms continue into July at higher elevations. Find and photograph a flower or two at each of these three sections of the Gorge:

Western Gorge:

Washougal-Troutdale to Stevenson-Cascade Locks

Central Gorge:

Stevenson-Cascade Locks to White Salmon-Hood River

Eastern Gorge:

White Salmon-Hood River to Maryhill –The Dalles

Need help identifying Gorge wildflowers? Check out long-time member Paul Slichter's website.

My wonder:

What’s your favorite wildflower? Where do you like to go to find it? #preservethewonder

Cultural Wonders

Cultural Wonders

Culture runs deep in the Columbia River Gorge—in some places reaching back 10,000 years or more. These three sites range for some of the oldest art to the newest.

Stonework along the Historic Columbia River Highway

From the 1870s to 1890s, stonemasons from Italy emigrated to Oregon to cut stone for the lock canal at Cascade Locks. They liked what they saw here, and stayed. From 1913 to 1922, they and subsequent generations of masons helped build the “poem in stone” that is the Columbia River Highway. Arched stone guardrails, stone walls, bridge facades, and roadside pullouts: the highway’s stonework is all hand-hewn and a huge factor in the beauty of this road, the nation’s first planned scenic highway. Today the entire length of the highway through the Gorge is a National Historic Landmark.Look for their work at the magnificent Eagle Creek bridge; it’s the only Historic Highway bridge faced in native rock; just downstream of the bridge is a beautiful, curving creekside overlook that makes a great place to watch salmon spawn. The rock wall below Vista House is spectacular, and pullouts on the road west of Vista House sport beautiful low stone walls. These are just a few spots where you can enjoy the hand-wrought stone on the Historic Highway.

Lewis & Clark Bird Blind

In the Sandy River Delta, a once-farmed floodplain is being restored with native plants. In this vast off-leash dog area, the Confluence Trail leads to Bird Blind, an art installation by the famed artist Maya Lin (who designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.). It’s one of several such installations along the Columbia River that are part of the Confluence Project. Bird Blind’s vertical slats, made of black locust, are inscribed with the names and current status of the 134 species that Lewis and Clark noted on their journey to the Pacific Ocean. It’s fun to compare the inventive spellings the men used with the species common and scientific names.Pictographs & Petroglyphs

The Eastern Gorge is known for its Native American rock art: petroglyphs, images incised in stone, and pictographs, paintings on stone using natural pigments.The famous “Tsagaglalal” or “She Who Watches” petroglyph was created centuries ago on a basalt cliff overlooking the Columbia River’s northern shore, where the Wishram people lived for 3,000 years. That land is now underwater. The Wishram tell her story:

A woman was chief of all who lived in this region. That was before Coyote came up the river and changed things, and the people were not yet real people. Coyote, in his travels, came to this place and asked the people if they were living well or ill. They sent him to their chief, who lived up in the rocks, where she could look down on the village and know what was going on.

Coyote climbed up to her house and asked, “What kind of living do you give these people? Do you treat them well or are you one of those evil women?”

“I am teaching them to live well and build good houses,” she said.

When she expressed her desire to be able to do this forever, he said, “Soon the world will change and women will no longer be chief.”

Being the trickster that he was, Coyote changed her into a rock with the command, “You shall stay here and watch over the people and the river forever.”

You can see “She Who Watches” in her original setting, now part of Columbia Hills State Park, but only on a guided tour, April to October. Call ahead for the popular tours: 509-767-1159. Other petroglyphs at the park can be seen without a reservation; they were removed from rocks soon to be inundated by The Dalles Dam in the 1950s.

On the 1.5-mile interpretive trail at Fort Cascades National Historic Site, located at the Lower Cascades of the Columbia (today’s North Bonneville), you can find a replica of a petroglyph once found at this site. The original now sits outside Stevenson’s Courthouse Annex, along Vancouver Avenue.

At Skamania Lodge, walk the halls in the common areas to see rubbings of petroglyphs that are on Columbia River islands and rocky cliffs. The rubbings were created by artist Jeanne Hillis in the years before the sites were inundated by The Dalles Dam.

My wonder:

What art or handcraft in the Gorge has caught your eye recently? #preservethewonder

Waterfall Wonders

For many Gorge visitors, it’s all about the falls. The Gorge has the densest concentration of waterfalls anywhere in North America. Spring—especially after this year’s high levels of rain and snow—is when Gorge waterfalls are at their most splendiferous. As a Pacific Northwesterner, it’s good to know which type of waterfall you’re looking at. Here are three common types seen in the Gorge:

Horsetail

Plunge

These waterfalls drop vertically, usually without touching the underlying cliff face. Sometimes the rock behind the falls is eroded enough that you can even walk behind the falling water. Multnomah, and Latourell are plunge-type falls.

These waterfalls drop vertically, usually without touching the underlying cliff face. Sometimes the rock behind the falls is eroded enough that you can even walk behind the falling water. Multnomah, and Latourell are plunge-type falls.

Tiers

These falls have more than one vertical drop; Wahkeena and Bridal Veil are in this category.

These falls have more than one vertical drop; Wahkeena and Bridal Veil are in this category.

My wonder:

What’s your favorite Gorge waterfall to visit? What time of year do you like to see the falls—in summer when you can enjoy the spray or in winter and spring when they’re running at full bore? #preservethewonder

Geographical Wonders

The Gorge is a geological work in progress. Sometimes change occurs slowly, over millions of years; sometimes it happens in events that instantly reshape the landscape, as with the Ice Age floods and the Bonneville Landslide. And into the present, rock fall and winter landslides are evidence that the Gorge is ever changing. Here are places to see the Gorge story written in the rocks.

Bonneville Landslide

In the Central Gorge, the enormous Cascade Landslide Complex covers nearly 14 square miles in Washington. The most recent major slide in the complex, the Bonneville Landslide, was most likely triggered by a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake hundreds of years ago. In that event, the south face of Table Mountain collapsed, sending debris roaring downhill. The huge debris flow shoved the Columbia River a mile to the south, creating a temporary rock dam and narrowing the river channel to its current tight confines. Behind this dam—called the Bridge of the Gods by Native Americans who saw this amazing spectacle—a lake formed which extended upriver to The Dalles area. The river eventually carried off most of the slide debris, but left behind enough to create a narrow, rapids-filled channel that later explorers named the Great Cascades of the Columbia.

Humans built another Bridge of the Gods in 1926 where the natural dam had been. Designed for the narrow cars and trucks of that early automotive age, this short and beautiful bridge offers an excellent place to see and understand the power of the great slide. It’s part of the 2,650-mile Pacific Crest Trail, and is the only Gorge bridge where walkers and bikers are allowed. Vehicles creep along at 15 mph, and pedestrians are not uncommon, so walk on out. Look up to the cliffs of Table Mountain and north to the rumply run-out of the landslide now occupied by North Bonneville. On the shores below the bridge are Native American fishing platforms, a design that’s little changed since this area echoed with the roar of whitewater. Upstream is Thunder Island, and at low water, rocky above-water remnants of the Great Cascades, now inundated by the waters pooling behind Bonneville Dam.

Coyote Wall: An Anticline Called a Syncline

When you’re walking or biking the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail west of Mosier, one reward comes early on. It’s a view of one of the Gorge’s most spectacular geologic formations, Coyote Wall. Though it’s commonly and mistakenly referred to as the “Syncline,” the vertical wall that plunges into the river is actually an anticline. It consists of horizontal layers of basalt, which have been uplifted by faulting; the wall’s downward curve toward the Columbia is caused by horizontal compression of those layers. Like a rug on a slippery floor when the ends are pushed together, the horizontal pressure caused the rock layers to fold, resulting in a system of convex ridges, called anticlines (Coyote Wall), and concave valleys, or synclines. The Columbia flows through a syncline at this location. The pattern continues on the Oregon side: the river runs through the Ortley Anticline between The Dalles and Mosier and the Bingen Anticline between Mosier and Hood River. Mosier sits in a syncline called the Mosier Syncline. Whether you travel east or west from Mosier, the rock layers climb with you.

Whatever you call it, it’s spectacular. You can hike atop the wall, or see its entire length from Mosier Plateau.

Glacial Erratics

Erratics are rocks transported to a site by glaciers—or in the case of the Gorge, by Ice Age floods—from beyond the local region. “Erratic” comes from the Latin “to stray.” In the last Ice Age, massive floods carried rocks from the Rocky Mountains into the Gorge, and even to the Willamette Valley, where they’ve been used as tombstones, fence walls or yard ornaments. The Gorge has many erratics, some known, others yet to be discovered. Some have been found as high as the 800-foot level, awesome evidence of the power and depths of the floodwaters. Find one, a large chunk of granite, in Mosier near the parking lot at the Mark O. Hatfield East Trailhead to the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail.

My wonder:

What site fills you with awe about the Gorge’s cataclysmic past? #preservethewonder

Recreational Wonders

Recreational Wonders

The Gorge has been a transportation corridor for as long as humans have occupied this part of the continent. Exploring it is a multi-dimensional adventure, especially if you connect with one or more of the nationally designated trails that run through the Gorge:

Ice Age National Scenic Trail

From the grand dalles of the Columbia west to the Troutdale-Washougal area, epic Ice Age floods scoured the Columbia River valley from a V-shape to a U-shape. When the floodwaters retreated, gently-dropping hills had been transformed into vertical cliffs.

Geologists had long believed the earth’s surface was sculpted only by gradual forces over millennia. In the 1920s, a young Harlan Bretz thought otherwise. He theorized that sudden, cataclysmic floods had shaped the landscapes of Eastern Washington and the Columbia Gorge. Bretz’s idea was sneered at for decades. Skepticism ebbed when the work of Joseph Pardee, who documented giant ripple marks of a vanished lake in Western Montana, were paired with Bretz’s theory, answering the question of the floods’ origin.

At Rowena Crest, look for two dry, round depressions in the plateau. Here, hundreds of feet above today’s river level, flood waters roared over the cliffs. The water, churning with rocks, ice, trees and sand, sometimes formed a vortex, much like an underwater tornado. This vortex, or kolk, plucked boulders out of the underlying bedrock, swirling them and other debris around the resulting void until a circular depression formed, called a kolk lake or pond. From Rowena Crest, you can see a kolk pond that you can swim in, on the river at Mayer State Park.

Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail

When you consider that the Corps of Discovery’s passage through the Gorge was powered only by muscle and water, it’s easy to feel the same immense sense of awe the two men felt. In the following essay, the bold-faced text signifies sites that the men and their entourage experienced. You have the same opportunity to make your own discoveries today.

Lewis & Clark Expedition through the Gorge

by Friends Executive Director Kevin Gorman

The Lewis & Clark Expedition entered the Columbia Gorge in October 1805. The expedition was into the seventeenth month of a journey to the Pacific that they thought would take six months. After an unexpectedly difficult journey over the Rocky Mountains, they expected a gentle float down the Columbia. Instead, they got Celilo Falls and the Great Cascades. The expedition passed the mouth of the Deschutes River on October 22 and took two days to portage 30 tons of gear around Celilo Falls. [Oregon’s Celilo Park is on the south bank of what was Celilo Falls until The Dalles Dam raised the river level here.]

Following the falls, they faced two series of rapids, the Short and Long Narrows, which were unlike any rapids, they had seen [between Celilo Park and The Dalles]. The men who couldn’t swim portaged gear while those who could rode the rapids. Their journals report that the Native Americans climbed the ledges to watch and had “much astonishment” to see the canoes make it through.

Once through the Narrows, they camped for three days at what they called Rock Fort, now found along The Dalles Riverfront Trail [close to downtown]. It is one of the only temporary campsites referred to as a “fort” as they choose this site for protection as much as convenience. They were heavily outnumbered, and the Native Americans here were very sophisticated in terms of trading and bargaining.

On October 30, they headed downstream near Dog Mountain and had their first sighting of the California condor, which they called the “butiful buzzard of the Columbia,” and measures over nine feet in wingspan. The expedition then came across another unusual site, this in the water rather than the air. On the journey back in April, Lewis writes:

“We find the trunks of many large pine trees standing erect as they grew at present in 30 feet of water; they are decayed and none of them vegetating. Certain it is that those large pine trees never grew in that position, nor can I account for this phenomenon except it be that the passage of the river through the narrow pass at the rapids has been obstructed by the rocks which have fallen from the hills into the channel within the last 20 years; the appearance of the hills at that place justify this opinion, they appear constantly to be falling in…”

What Lewis suggests is exactly what happened. Geologists believe that anywhere from 300 – 800 years ago, several of the mountain faces broke off and came sliding down, pushing the river one mile to the south and effectively damming it, at least for a few days. The damming ties to the Indian legend of the Bridge of the Gods and it would have flooded hundreds of acres of forests upstream.

After enduring the Short and Long Narrows, the expedition decided to portage around the Cascades [which ranged from today’s Cascade Locks downriver to the site of Bonneville Lock and Dam]. It took them two days, but once through they literally did experience smooth sailing until they approached the ocean. Just past the Cascades, they named and investigated Beacon Rock. It was also at Beacon Rock where they noted the tidal influence on the river. They knew they were getting close to the ocean.

They then approached what many consider to be the most beautiful section of the Gorge, the waterfalls area and say little about it in their journals. Part of that is likely due to the rain, wind and cold, but it is also quite possible that bad weather obscured Multnomah Falls and they did not see until the return trip.

They proceeded on to the ocean, where they took the famous vote of whether to make camp on the Oregon coast, the Washington coast, or back up the Gorge. The vote was famous because all the participants, including Sacegwea and Clark’s slave York, had a vote. They chose the Oregon coast because there seemed to be more elk and deer in Oregon and a ship called the Lydia was expected that winter and they hoped to sail their way back to civilization. The ship arrived about two weeks after they left Fort Clatsop in the spring and began the journey back.

They were back near the mouth of the Sandy [at Troutdale] on March 31 and camped across the river in Washington, thrilled to be out of the forested prison they called Fort Clatsop. While there, they received word from Indians upstream that the salmon were not running yet and the upstream tribes were starving. So they made camp for six days near present day Washougal [at Cottonwood Beach in Captain William Clark Park] and hunted and dried more meat.

By April 6, they moved upstream to the area of Shepperd’s Dell to hunt elk. An elk herd still resides in the area today. As they were now taking their time and had good weather, the journals turned their focus on the beauty of the scenery. Lewis wrote:

“…We passed several beautifull cascades…the most remarkable of these cascades falls [Multnomah Falls] about 300 feet perpendicularly over the solid rock into a narrow bottom of the river on the south side.”

He was only off by about 300 feet.

Portaging up the Great Cascades took three days. [They would’ve encountered their first rapid of the Cascades at about the mouth of Tanner Creek.] Throughout their travels in the Gorge, the expedition continually had equipment stolen from them by the tribes. Stolen would be Lewis & Clark’s vernacular. To the tribes, everyone paid a toll when coming through, and anyone with a great abundance of items would of course share with those who had less. So when an item was put down on the ground to dry, it was deemed fair game.

Well the ultimate insult occurred when Captain Lewis’ Newfoundland dog Seaman was stolen. Now considering the expedition had been trading for and eating dogs throughout their travels, you might think it wouldn’t be a big deal. Well it was. Lewis was furious and gave orders to retrieve the dog even if lives needed to be taken. Fortunately, no blood was shed and his dog was soon back with the group.

On April 13, the expedition camped at the base of Dog Mountain; at this point they note the change in scenery and are obviously pleased to get out of the thick forest. The next evening they pulled into a small tributary now called Major Creek to camp for the night [on the Washington shore, the next creek upriver from Catherine Creek]. Our founder Nancy Russell bought this property to preserve it and it is now public land.

The next day, the expedition paddled out to what they called Sepulcher Island. It is now called Memaloose Island, meaning Island of the Dead [See it from the Memaloose Overlook on the Historic Highway east of Mosier]. In this area of the Gorge, with little or no soil, islands were the typical repositories for the dead. The remains of the Native Americans have since been removed. From Memaloose Island, they proceeded east.

Back in the area around The Dalles, the fish had finally returned and Lewis and Clark witnessed a sacred tradition. The first fish caught from the returning run was brought into the village and all the children were assembled. The one fish was cooked and a small portion of that fish was given to every child in the village. Until that fish was eaten, no more fish could be caught. This was a form of blessing and a way to ensure a strong run of fish.

At this point, clear of the forests, they were ready to trade their canoes in for horses and make the journey overland. But what they discovered is that the Indians realized Lewis & Clark desperately needed horses, and that they would eventually have to give the Indians much more than they wanted to in order to get the horses. This aggressive bargaining was not what Lewis had bargained for. Just to show what a gracious negotiator he was, Lewis ordered his men to cut up and burn one of the canoes that they couldn’t trade so no one would ever use it. They then camped near the present Columbia Hills Lake State Park, home to amazing petroglyphs including “She Who Watches.”

From that point, they broke camp and spent one more night in the Gorge, before pushing on. While the trip to the coast took eighteen months, the trip back only took six months and they returned to St. Louis in the fall of 1806 to a hero’s welcome as the world had assumed they had perished on their long journey.

Oregon National Historic Trail

Beginning in the 1840s, emigrants on the Oregon Trail stopped to rest at the tiny settlement at the dalles of the Columbia. Until 1845, their only option for the last leg of the trip was the Columbia River. Death, mayhem and loss of precious cargo roped onto open rafts might lie ahead. The river’s rapids and winds were formidable foes. Most pioneers reached The Dalles area in late summer, when days are scorching hot and the land is parched. Visit these sites, and try to imagine the fear and fatigue that must have walked with the pioneers each day.

On Highway 206, 2.2 miles east of the Deschutes River, the Oregon Trail descends to the road. At an Oregon Trail marker on the road’s south side, walk beyond a gate and uphill for .18 mile on a section of unimproved trail. Further west, a pioneer-era wagon and interpretive signs at Deschutes River State Recreation Area tell the story of the treacherous ford at the Deschutes.

Follow the pioneers’ path west of the Deschutes by driving Moody Road uphill 1.5 dusty miles to a plateau overlooking Celilo Falls. The steep hill is an easy journey in a car, but must have been discouraging to the tired emigrants. Follow the road to Fairbanks Gap and then along 15 Mile Road into The Dalles. Both roads are laid down over the Oregon Trail. At The Dalles, visit The Dalles Wahtonka High School; it sits at the site of a spring where Methodists founded a mission in 1836. Here pioneers rested before the final leg of their journey.

Along the Riverfront Trail—a paved pedestrian path—in The Dalles is Rock Fort. See Kevin Gorman’s essay, above.

Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail

Hike a segment of this 2,650-mile trail that is one of the original National Scenic Trails established in 1968 by Congress. In the Gorge, the PCT runs north-south for 25 miles. You can find PCT trail loops at www.pcta.org: in Washington at Snag Creek and Trout Creek; in Oregon at Dry Creek Falls and Herman Creek. Cascade Locks is the only incorporated city on the entire length of the trail; its Bridge of the Gods is a trail highlight (it’s described in "Bonneville Landslide," above). Every August the town hosts PCT Days, a festival all about outdoor recreation. View a map of PCT hikes in the Gorge.

My Wonder

What is your favorite trail in the Gorge? What makes it so special? #preservethewonder